Let’s compare mental capacity vs mental competence.

I’m on a mission to think better.

We’re all born with certain limitations. However, we underestimate how much better thinkers we can become by taking a more strategic approach to one of the most fundamental human activities—thinking.

Here we go:

Mental Capacity vs Mental Competence

As a PR professional, I often meet with experienced, intelligent, ambitious, conscientious, creative, and highly motivated decision-makers. If you have the financial mandate to invest in public relations counsel, you’re likely to be a person of substance.

Still, I’m amazed almost daily at how otherwise accomplished individuals fall prey to logical fallacies and cognitive biases so frequently. At first, I thought that this meant that I was very clever — until I realised that I was just as stupid as often as they were.

What’s going on here?

To explore thinking better, I would like to make an essential distinction:

Intelligence. This measure is based on mental capacity (genetics, epigenetics, and neuroplasticity).

Clear thinking. This skill is based on mental competence (knowledge, experience, and practice).

Using this distinction, we might find that improving mental capacity is challenging. Your genetics are what they are — for better or worse. Still, interesting scientific insights stemming from research on epigenetics and neuroplasticity exist.

There are also different intelligence types. While you might be weaker in some intellectual capacities, you might be unknowingly strong in others you haven’t yet explored or developed.

As for mental competence, there are countless different venues to investigate and learn. You can learn powerful mental models to think better and faster. You can learn more about different types of knowledge and how knowledge is created.

You can rid yourself of bad thinking habits and learn to recognise logical fallacies and cognitive biases.

In short:

There are many ways to be smart.

Learn more: Mental Capacity vs Mental Competence

10 Intelligence Types

Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences expands the traditional view of intelligence beyond logical and linguistic capabilities. 1Theory of multiple intelligences. (2023, November 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_multiple_intelligences

“Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences has revolutionized education, challenging the notion of a single, fixed intelligence and promoting a more diverse approach to teaching and learning.”

Source: The First Seven…and the Eighth: A Conversation with Howard Gardner 2Checkley, K. (1997). The First Seven…and the Eighth: A Conversation with Howard Gardner. Educational Leadership, 55, 8 – 13.

Here’s a description of each type of intelligence as outlined in his theory:

Each intelligence type represents different ways of processing information and suggests everyone has a unique blend of these bits of intelligence. 4Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books.

Learn more: 10 Intelligence Types

Mental Models: Think Better

Mental models emphasise the importance of viewing problems from multiple perspectives, recognising personal limitations, and understanding the often unforeseen interactions between different factors.

The writings of Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and long-time collaborator of Warren Buffett and many others, inspire several of the below models.5It’s worth noting that these models are not exclusively Charlie Munger’s inventions but tools he advocates for effective thinking and decision-making.

List of Mental Models

Here’s a list of my favourite mental models:

The iron prescription (mental model). Senior advisor Charlie Munger argued: “I have what I call an ‘iron prescription’ that helps me keep sane when I naturally drift toward preferring one ideology over another. I feel that I’m not entitled to have an opinion unless I can state the arguments against my position better than the people who are in opposition. I think that I am qualified to speak only when I’ve reached that state” (Knodell, 2016). 6Knodell, P. A. (2016). All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there: Buffett & Munger – A study in simplicity and uncommon, common sense. PAK Publishing.

The Red Queen effect (mental model). This metaphor originates from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass. It describes a situation in which one must continuously adapt, evolve, and work to maintain one’s position. In the story, the Red Queen is a character who explains to Alice that in their world, running as fast as one can is necessary just to stay in the same place. The metaphor is often used in the context of businesses that need to innovate constantly to stay competitive, highlighting the relentless pressure to adapt in dynamic environments where stagnation can mean falling behind. 7Red Queen hypothesis. (2023, November 27). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Queen_hypothesis 8Carroll, L. (2006). Through the looking-glass, and what Alice found there (R. D. Martin, Ed.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1871.)

Ockam’s razor (mental model). This principle suggests that the simplest explanation is usually correct. The one with the fewest assumptions should be selected when presented with competing hypotheses. It’s a tool for cutting through complexity and focusing on what’s most likely true. 9Ariew, R. (1976). Ockham’s Razor: A historical and philosophical analysis of simplicity in science. Scientific American, 234(3), 88 – 93.

Hanlon’s razor (mental model). This thinking aid advises against attributing to malice what can be adequately explained by incompetence or mistake. It reminds us to look for more straightforward explanations before jumping to conclusions about someone’s intentions. 10Hanlon, R. J. (1980). Murphy’s Law book two: More reasons why things go wrong!. Los Angeles: Price Stern Sloan.

Vaguely right vs precisely wrong (mental model). This principle suggests it is better to be approximately correct than 100% incorrect. In many situations, seeking precision can lead to errors if the underlying assumptions or data are flawed. Sometimes, a rough estimate is more valuable than a precise but potentially misleading figure. 11Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. London: Macmillan.

Fat pitch (mental model). Borrowed from baseball, this concept refers to waiting patiently for the perfect opportunity — a situation where the chances of success are exceptionally high. It suggests the importance of patience and striking when the time is right. 12Kaufman, P. A. (Ed.). (2005). Poor Charlie’s almanack: The wit and wisdom of Charles T. Munger. Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company Publishers.

Chesterton’s fence (mental model). G.K. Chesterton: ”In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it” (Chesterton, 1929). 13Chesterton, G. K. (1929). “The Drift from Domesticity”. Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine In: The Thing. London: Sheed & Ward, p. 35

First-conclusion bias (mental model). This is the tendency to stick with the first conclusion without considering alternative possibilities or additional information. It’s a cognitive bias that can impede critical thinking and thorough analysis.

First principles thinking (mental model). This approach involves breaking down complex problems into their most basic elements and then reassembling them from the ground up. It’s about getting to the fundamental truths of a situation and building your understanding from there rather than relying on assumptions or conventional wisdom.

The map is not the territory (mental model). This model reminds us that representations of reality are not reality itself. Maps, models, and descriptions are simplifications and cannot capture every aspect of the actual territory or situation. It’s a caution against over-relying on models and theories without considering the nuances of real-world situations. 14Silfwer, J. (2022, November 3). Walter Lippmann: Public Opinion and Perception Management. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/walter-lippmann/

Bell curve (mental model). This curve is a graphical depiction of a normal distribution, showing how many occurrences fall near the mean value and fewer occur as you move away from the mean. In decision-making, it’s used to understand and anticipate variability and to recognise that while extreme cases exist, most outcomes will cluster around the average.

Compounding (mental model). Often used in the context of finance, compounding refers to the process where the value of an investment increases because the earnings on an investment, both capital gains and interest, earn interest as time passes. This principle can be applied more broadly to understand how small, consistent efforts can yield significant long-term results.

Survival of the fittest (mental model). Borrowed from evolutionary biology, this mental model suggests that only those best adapted to their environment survive and thrive. In a business context, it can refer to companies that adapt to changing market conditions and are more likely to succeed.

Mr. Market (mental model). A metaphor created by Benjamin Graham represents the stock market’s mood swings from optimism to pessimism. It’s used to illustrate emotional reactions in the market and the importance of maintaining objectivity. 15Graham, B. (2006). The intelligent investor: The definitive book on value investing (Rev. ed., updated with new commentary by J. Zweig). Harper Business. (Original work published 1949.)

Second-order thinking (mental model). This kind of thinking goes beyond the immediate effects of an action to consider the subsequent effects. It’s about thinking ahead and understanding the longer-term consequences of decisions beyond just the immediate results.

Law of diminishing returns (mental model). This economic principle states that as investment in a particular area increases, the rate of profit from that investment, after a certain point, cannot increase proportionally and may even decrease. It’s essential to understand when additional investment yields progressively smaller returns. 16Diminishing returns. (2024, November 15). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diminishing_returns

Opportunity cost (mental model). This concept refers to the potential benefits one misses out on when choosing one alternative over another. It’s the cost of the following best option foregone. Understanding opportunity costs helps make informed decisions by considering what to give up when choosing.

Swiss Army knife approach (mental model). This concept emphasises the importance of having diverse tools (or skills). Being versatile and adaptable in various situations is valuable, like a Swiss Army knife. This model is beneficial for uncertain and volatile situations. There’s also a case to be made for generalists in a specialised world. 17Parsons, M., & Pearson-Freeland, M. (Hosts). (2021, August 8). Charlie Munger: Latticework of mental models (No. 139) [Audio podcast episode]. In Moonshots podcast: Learning out … Continue reading 18Epstein, D. (2019). Range: Why generalists triumph in a specialized world. Riverhead Books.

Acceleration theory (mental model). This concept indicates that the winner mustn’t lead the race from start to finish. Mathematically, delaying maximum “speed” by prolonging the slower acceleration phase will get you across the finish line faster. 19Silfwer, J. (2012, October 31). The Acceleration Theory: Use Momentum To Finish First. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/acceleration-theory/

Manage expectations (mental model). This concept involves setting realistic expectations for yourself and others. It’s about aligning hopes and predictions with what is achievable and probable, thus reducing disappointment and increasing satisfaction. Effective expectation management can lead to better personal and professional relationships and outcomes.

Techlash (mental model). This mental model acknowledges that while technology can provide solutions, it almost always creates foreseen and unforeseen problems. It’s a reminder to approach technological innovations cautiously, considering potential negative impacts alongside the benefits. 20Silfwer, J. (2018, December 27). The Techlash: Our Great Confusion. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/techlash/

World’s most intelligent question (mental model). This mental model refers to repeatedly asking “Why?” to delve deeper into a problem and understand its root causes. By continually asking why something happens, one can uncover layers of understanding that might remain hidden.

Regression to the mean (mental model). This statistical principle states that extreme events are likely to be followed by more moderate ones. Over time, values tend to revert to the average, a concept relevant in many areas, from sports performance to business metrics.

False dichotomy (mental model). This logical fallacy occurs when a situation is presented as having only two exclusive and mutually exhaustive options when other possibilities exist. It oversimplifies complex issues into an “either/or” choice. For instance, saying, “You are either with us or against us,” ignores the possibility of neutral or alternative positions.

Inversion (mental model). Inversion involves looking at problems backwards or from the end goal. Instead of thinking about how to achieve something, you consider what would prevent it from happening. This can reveal hidden obstacles and alternative solutions.

Psychology of human misjudgment (mental model). This mental model refers to understanding the typical biases and errors in human thinking. One can make more rational and objective decisions by knowing how cognitive biases, like confirmation bias or the anchoring effect, can lead to flawed reasoning.

Slow is smooth, smooth is fast (mental model). — Often used in military and tactical training, this phrase encapsulates the idea that sometimes, slowing down can lead to faster overall progress. The principle is that taking deliberate, considered actions reduces mistakes and inefficiencies, which can lead to faster outcomes in the long run. In practice, it means planning, training, and executing with care, leading to smoother, more efficient operations that achieve objectives faster than rushed, less thoughtful efforts. 21Silfwer, J. (2020, April 24). Slow is Smooth, Smooth is Fast. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/slow-is-smooth/

Because you are worth it (mental model). This mental model focuses on self-worth and investing in oneself. It suggests recognising and affirming one’s value is crucial for personal growth, happiness, and success. This can involve self-care, education, or simply making choices that reflect one’s value and potential.

Physics envy (mental model). This term describes the desire to apply the precision and certainty of physics to fields where such exactitude is impossible, like economics or social sciences. It’s a caution against overreliance on quantitative methods in areas where qualitative aspects play a significant role.

Easy street strategy (mental model). This principle suggests that simpler solutions are often better and more effective than complex ones. In decision-making and problem-solving, seeking straightforward, clear-cut solutions can often lead to better outcomes than pursuing overly complicated strategies. 22Silfwer, J. (2021, January 27). The Easy Street PR Strategy: Keep It Simple To Win. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/easy-street-pr-strategy/

Scale is key (mental model). This concept highlights how the impact of decisions or actions can vary dramatically depending on their scale. What works well on a small scale might not be practical or feasible on a larger scale, and vice versa.

Circle of competence (mental model). This concept involves recognising and understanding one’s areas of expertise and limitations. The idea is to focus on areas where you have the most knowledge and experience rather than venturing into fields where you lack expertise, thereby increasing the likelihood of success.

Fail fast, fail often (mental model). By failing fast, you quickly learn what doesn’t work, which helps in refining your approach or pivoting to something more promising. Failing often is seen not as a series of setbacks but as a necessary part of the process towards success. This mindset encourages experimentation, risk-taking, and learning from mistakes, emphasising agility and adaptability.

Correlation does not equal causation (mental model). This principle is a critical reminder in data analysis and scientific research. Just because two variables show a correlation (they seem to move together or oppose each other) does not mean one causes the other. Other variables could be at play, or it might be a coincidence.

Critical mass (mental model). This mental model emphasises the importance of reaching a certain threshold to trigger a significant change, whether user adoption, market penetration, or social movement growth. This model guides strategic decisions, such as resource allocation, marketing strategies, and timing of initiatives, to effectively reach and surpass this crucial point. 23Silfwer, J. (2019, March 10). Critical Mass: How Many Social Media Followers Do You Need? Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/critical-mass-followers/

Sorites paradox (mental model). Also known as the paradox of the heap, this paradox arises from vague predicates. It involves a sequence of small changes that don’t seem to make a difference individually but, when accumulated, lead to a significant change where the exact point of change is indiscernible. For example, if you keep removing grains of sand from a heap, when does it stop being a heap? Each grain doesn’t seem to make a difference, but eventually, you’re left with no heap.

The power of cycle times (mental model). Mathematically, reducing cycle times in a process that grows exponentially (like content sharing on social networks) drastically increases the growth rate, leading to faster and broader dissemination of the content, thereby driving virality. The combination of exponential growth, network effects, and feedback loops makes cycle time a critical factor. 24Let’s say the number of new social media shares per cycle is a constant multiplier, m. If the cycle time is t and the total time under consideration is T, the number of cycles in this time is T/t. … Continue reading 25Silfwer, J. (2017, February 6). Viral Loops (or How to Incentivise Social Media Sharing). Doctor Spin | the PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/viral-loop/

Non-linearity (mental model). This mental model recognises that outcomes in many situations are not directly proportional to the inputs or efforts. It suggests that effects can be disproportionate to their causes, either escalating rapidly with minor changes or remaining stagnant despite significant efforts. Understanding non-linearity helps in recognising and anticipating complex patterns in various phenomena.

Checklists (mental model). This mental model stresses the importance of systematic approaches to prevent mistakes and oversights. Using checklists in complex or repetitive tasks ensures that all necessary steps are followed and nothing is overlooked, thereby increasing efficiency and accuracy. 26Silfwer, J. (2020, September 18). Communicative Leadership in Organisations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/communicative-leadership/

Lollapalooza (mental model). Coined by Munger, this term refers to situations where multiple factors, tendencies, or biases interact so that the combined effect is much greater than the sum of individual effects. It’s a reminder of how various elements can converge to create significant impacts, often unexpected or unprecedented.

Limits (mental model). This mental model acknowledges that everything has boundaries or limits, beyond which there can be negative consequences. Recognising and respecting personal, professional, and physical limits is essential for sustainable growth and success. In the words of “Dirty Harry” Callahan, “A man’s got to know his limitations.”

The 7Ws (mental model). This mental model refers to the practice of asking “Who, What, When, Where, Why” (and sometimes “How”) to understand a situation or problem fully. By systematically addressing these questions, one can comprehensively understand an issue’s context, causes, and potential solutions, leading to more informed decision-making. 27Silfwer, J. (2020, September 18). The Checklist for Communicative Organisations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/checklist-for-communicative-leadership/

Chauffeur knowledge (mental model). This mental model distinguishes between having a surface-level understanding (like a chauffeur who knows the route) and deep, genuine knowledge (like an expert who understands the intricacies of a subject). It warns against the illusion of expertise based on superficial knowledge and emphasises the importance of accurate, deep understanding.

Make friends with eminent dead (mental model). This mental model advocates learning from the past, particularly from significant historical figures and their writings. Studying the experiences and thoughts of those who have excelled in their fields can yield valuable insights and wisdom.

Seizing the middle (mental model). This strategy involves finding and maintaining a balanced, moderate position, especially in conflict or negotiation. It’s about avoiding extremes and finding a sustainable, middle-ground solution. Also, centre positions often offer the broadest range of options.

Asymmetric warfare (mental model). This refers to conflict between parties of unequal strength, where the weaker party uses unconventional tactics to exploit the vulnerabilities of the stronger opponent. It’s often discussed in military and business contexts.

Boredom syndrome (mental model). This term refers to the human tendency to seek stimulation or change when things become routine or monotonous, which can lead to unnecessary changes or risks. Sometimes, taking no action is better than taking action, but remaining idle can be difficult.

Survivorship bias (mental model). This cognitive bias involves focusing on people or things that have “survived” some process and inadvertently overlooking those that did not due to their lack of visibility. This can lead to false conclusions because it ignores the experiences of those who did not make it through the process. 28Silfwer, J. (2019, October 17). Survivorship Bias. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/survivorship-bias/

Each mental model offers a lens for viewing problems, making decisions, and strategising, reflecting the complexity and diversity of thought required in various fields and situations.

Numerous other mental models are also used in various fields, such as economics, psychology, and systems thinking.

Learn more: Mental Models: How To Think Better

How To Create Knowledge

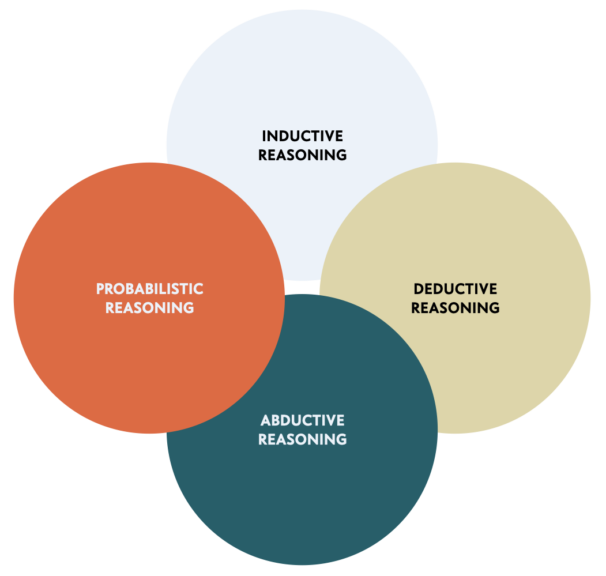

This list of how to create knowledge presents aspects of reasoning, methodological approaches, data analysis perspectives, and philosophical frameworks. It explains how knowledge can be approached, analysed, and interpreted.

Types of Reasoning and Logical Processes

Methodological Approaches

Data and Analysis Perspectives

Philosophical and Theoretical Frameworks

Learn more: How To Create Knowledge

Types of Bad Thinking Habits

Underpinning most of our thinking mistakes, some psychologically induced thinking habits seem to affect our ability to think clearly. Understanding (and avoiding) these behavioural patterns should allow for clear thinking.

Understanding these different types of thinking can help identify and address cognitive fallacies and biases in decision-making and problem-solving processes.

Learn more: Types of Bad Thinking Habits

Learn more: Logical Fallacies and Cognitive Biases

List of Logical Fallacies and Biases

We easily fall prey to the tricks our psychology plays on us. These “thinking errors” exist because they’ve often aided our survival. However, knowing and understanding various types of common fallacies and biases is helpful in everyday life.

Here are a few examples of logical fallacies and biases that I’ve come across while studying public relations and linguistics:

Learn more: 58 Logical Fallacies and Biases

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

What should you study next?

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Improvement: Renaissance Projects

The Renaissance lasted from the 14th to the 17th century and was a period of significant cultural, artistic, political, and scientific rebirth in Europe.

Inspired by the Renaissance mindset, I strive to develop my creative intelligence, physical strengths, and mental well-being.

Better Identity

Better Thinking

Better Skills

Better Habits

Learn more: Creativity

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

Annotations

| 1 | Theory of multiple intelligences. (2023, November 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_multiple_intelligences |

|---|---|

| 2 | Checkley, K. (1997). The First Seven…and the Eighth: A Conversation with Howard Gardner. Educational Leadership, 55, 8 – 13. |

| 3 | See also: Silfwer, J. (2023, April 25). Theory of Mind: A Superpower for PR Professionals. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/theory-of-mind-a-superpower-for-pr-professionals/ |

| 4 | Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books. |

| 5 | It’s worth noting that these models are not exclusively Charlie Munger’s inventions but tools he advocates for effective thinking and decision-making. |

| 6 | Knodell, P. A. (2016). All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there: Buffett & Munger – A study in simplicity and uncommon, common sense. PAK Publishing. |

| 7 | Red Queen hypothesis. (2023, November 27). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Queen_hypothesis |

| 8 | Carroll, L. (2006). Through the looking-glass, and what Alice found there (R. D. Martin, Ed.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1871.) |

| 9 | Ariew, R. (1976). Ockham’s Razor: A historical and philosophical analysis of simplicity in science. Scientific American, 234(3), 88 – 93. |

| 10 | Hanlon, R. J. (1980). Murphy’s Law book two: More reasons why things go wrong!. Los Angeles: Price Stern Sloan. |

| 11 | Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. London: Macmillan. |

| 12 | Kaufman, P. A. (Ed.). (2005). Poor Charlie’s almanack: The wit and wisdom of Charles T. Munger. Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company Publishers. |

| 13 | Chesterton, G. K. (1929). “The Drift from Domesticity”. Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine In: The Thing. London: Sheed & Ward, p. 35 |

| 14 | Silfwer, J. (2022, November 3). Walter Lippmann: Public Opinion and Perception Management. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/walter-lippmann/ |

| 15 | Graham, B. (2006). The intelligent investor: The definitive book on value investing (Rev. ed., updated with new commentary by J. Zweig). Harper Business. (Original work published 1949.) |

| 16 | Diminishing returns. (2024, November 15). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diminishing_returns |

| 17 | Parsons, M., & Pearson-Freeland, M. (Hosts). (2021, August 8). Charlie Munger: Latticework of mental models (No. 139) [Audio podcast episode]. In Moonshots podcast: Learning out loud. Moonshots. https://www.moonshots.io/episode-139-charlie-munger-latticework-of-mental-models |

| 18 | Epstein, D. (2019). Range: Why generalists triumph in a specialized world. Riverhead Books. |

| 19 | Silfwer, J. (2012, October 31). The Acceleration Theory: Use Momentum To Finish First. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/acceleration-theory/ |

| 20 | Silfwer, J. (2018, December 27). The Techlash: Our Great Confusion. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/techlash/ |

| 21 | Silfwer, J. (2020, April 24). Slow is Smooth, Smooth is Fast. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/slow-is-smooth/ |

| 22 | Silfwer, J. (2021, January 27). The Easy Street PR Strategy: Keep It Simple To Win. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/easy-street-pr-strategy/ |

| 23 | Silfwer, J. (2019, March 10). Critical Mass: How Many Social Media Followers Do You Need? Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/critical-mass-followers/ |

| 24 | Let’s say the number of new social media shares per cycle is a constant multiplier, m. If the cycle time is t and the total time under consideration is T, the number of cycles in this time is T/t. The total reach after time T can be approximated by m(T/t), assuming one initial share. When t decreases, T/t increases, meaning more cycles occur in the same total time, T. This leads to a higher m power in the expression m(T/t), which means a more extensive reach. |

| 25 | Silfwer, J. (2017, February 6). Viral Loops (or How to Incentivise Social Media Sharing). Doctor Spin | the PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/viral-loop/ |

| 26 | Silfwer, J. (2020, September 18). Communicative Leadership in Organisations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/communicative-leadership/ |

| 27 | Silfwer, J. (2020, September 18). The Checklist for Communicative Organisations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/checklist-for-communicative-leadership/ |

| 28 | Silfwer, J. (2019, October 17). Survivorship Bias. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/survivorship-bias/ |