The conversion theory has strong psychological effects.

The conversion theory explains why minorities can be powerful beyond their numbers.

How does the conversion theory work?

Here we go:

The Conversion Theory

The social psychologist Serge Moscovici found that we become more engaged if we belong to a misrepresented minority.

The disproportional power of minorities is known as the conversion theory. 1Conversion theory of minority influence. (2021, February 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conversion_theory_of_minority_influence

“In groups, the minority can have a disproportionate effect, converting many ‘majority’ members to their own cause. This is because many majority group members are not strong believers in its cause. They may be simply going along because it seems easier or that there is no real alternative. They may also have become disillusioned with the group purpose, process, or leadership and are seeking a viable alternative.”

Source: Changingminds.org 2Conversion Theory. (2023). Changingminds.org. https://changingminds.org/explanations/theories/conversion_theory.htm

How does it work?

The social cost of holding a different view than the majority is high. This increased cost explains why minorities often hold their opinions more firmly. It takes determination to go against the norm. 3Moscovici, S. (1980). Toward a theory of conversion behaviour. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 209 – 239. New York: Academic Press

In contrast, many majority members don’t hold their opinions so firmly. They might belong to the majority for no other reason than that everyone else seems to be. 4Chryssochoou, X. and Volpato, C. (2004). Social Influence and the Power of Minorities: An Analysis of the Communist Manifesto, Social Justice Research, 17, 4, 357 – 388

According to conversion theory, while majorities often claim normative social influence, minorities strive for ethical high ground.

Conversion Theory Examples

Given the power of normative social influence, minorities typically form tight-knit groups that can gather around a core message.

Most big shifts usually start with a small group of dedicated people:

Minority Influence: A PR Approach

Organisations with CSR aspirations can cultivate a sense of purpose and accomplishment among participants by aligning with a movement that challenges a stupid majority.

Since we tend to favour underdogs, liaising with a carefully selected minority can be a game-changing PR strategy.

Minority spokespersons with solid convictions often possess valuable knowledge and authority, enhancing their persuasive abilities and influence.

Disproportionately, minorities can convert numerous majority members to their cause, as many in the majority may have merely followed the path of least resistance, made decisions without much consideration, or lacked viable alternatives.

Additionally, a significant segment of the majority might be disillusioned with their group’s purpose, process, or leadership, rendering them more receptive to alternative proposals.

Proceed With Caution, Please

As PR professionals, we must be cautious when implementing the conversion theory.

Minorities aren’t always right, and majorities aren’t always wrong. Minorities can hold futile views while still exercising a disproportionate amount of power.

Learn more: Conversion Theory: The Disproportionate Influence of Minorities

Backfire Effect (or “Belief Perseverance” or “Conversion Theory” or “Amplification Hypothesis”)

The backfire effect (see also belief perseverance, conversion theory, and amplification hypothesis) occurs when individuals confronted with evidence that contradicts their beliefs or opinions become even more entrenched in those beliefs. Instead of adjusting their views based on new information, they react defensively and reject the contradictory evidence, often intensifying their original stance.

Backfire effect (example): “I presented solid data showing that the current marketing strategy isn’t working, but the team doubled down, insisting it’s the right approach and dismissing the data as flawed.”

In a business context, the backfire effect can be highly detrimental, preventing organisations from evolving and adapting to changing circumstances. By refusing to accept valid feedback or data that challenges their assumptions, teams may continue down ineffective paths, wasting resources or missing out on opportunities for improvement.

To counteract the backfire effect, business leaders should foster a culture of intellectual humility and openness, where feedback is welcomed and critically examined rather than rejected outright.

Encouraging a growth mindset, where learning and adaptation are prioritised over being “right,” helps create an environment where new ideas can be tested, and decisions are informed by evidence and reason. By promoting open dialogue and ensuring that evidence is evaluated objectively, organizations can avoid the pitfalls of the backfire effect and make more rational, data-driven decisions.

When confronted with a mirror of truth, many will look away to safeguard the integrity of their imagined reflections.

Learn more: The Conversion Theory

Learn more: The Amplification Hypothesis

The Stupid Majority PR Strategy

From what the conversion theory teaches us, minorities tend to hold their opinions more firmly. This is reasonable since going against the majority comes at a higher social cost. 5Silfwer, J. (2017, June 13). Conversion Theory — Disproportionate Minority Influence. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/conversion-theory/

But some minorities have an additional advantage:

Smart minority = a minority of today that will grow into a new majority of tomorrow.

In contrast, some majorities have an additional disadvantage:

Stupid majority = a majority of today that will steadily decline into a minority of tomorrow.

Identifying a stupid majority (and siding with a smart minority) will clarify your core message and attract highly engaged minority supporters.

Examples of Stupid Majorities

Stupid majorities are to be found everywhere:

Now, here’s the 1,000,000 EUR question:

What’s a stupid majority in your industry?

Challenging a Stupid Majority

Stupid majorities exist in your industry, too.

And now that you know what to look for, you’ll soon start finding them everywhere.

The stupid majority PR strategy could result in the most profound results of your public relations career:

Read also: The Stupid Majority PR Strategy

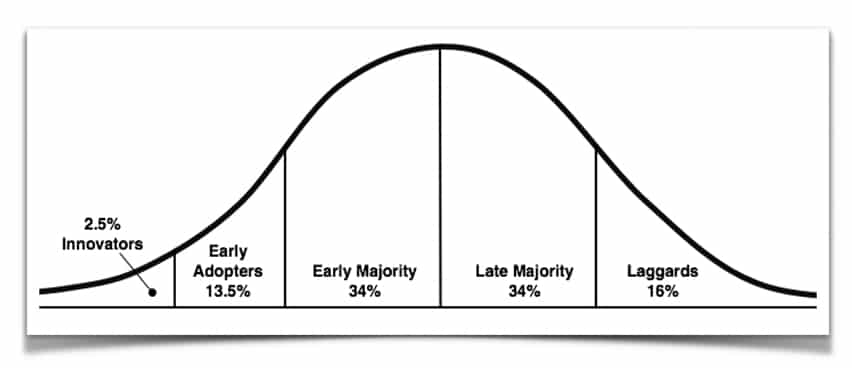

Diffusion of Innovations

The diffusion of innovations theory, proposed by Everett Rogers in 1962, remains a framework for understanding how new ideas, technologies, products, or practices spread through societies over time. 6Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

The diffusion of innovations theory outlines the process by which innovations are adopted by individuals and groups, emphasising the role of communication channels, social networks, and the characteristics of the innovation itself.

The diffusion of innovations theory offers insights into how new ideas and technologies influence societies. Understanding these dynamics can inform public relations strategies across diverse contexts.

“Diffusion research has helped understand new product adoption and diffusion, with network analysis and field experiments being promising tools in understanding the consumption of new products.”

Source: Journal of Consumer Research 7Rogers, E. (1976). New Product Adoption and Diffusion. Journal of Consumer Research, 2, 290 – 301. https://doi.org/10.1086/208642

Examples of Technological Adoptions

By examining real-life examples, we can better comprehend the principles of this theory and its applications in various fields:

Learn more: Diffusion of Innovations

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

What should you study next?

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Spin’s PR School: Free Media PR Course

Elevate your public relations skills with this free Media PR Course—a must-have resource for all aspiring public relations professionals. Boost your career now!

Media Theory

Media Logic

Journalism

Digital Media

Learn more: All Free PR Courses

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

Annotations

| 1 | Conversion theory of minority influence. (2021, February 12). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conversion_theory_of_minority_influence |

|---|---|

| 2 | Conversion Theory. (2023). Changingminds.org. https://changingminds.org/explanations/theories/conversion_theory.htm |

| 3 | Moscovici, S. (1980). Toward a theory of conversion behaviour. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 209 – 239. New York: Academic Press |

| 4 | Chryssochoou, X. and Volpato, C. (2004). Social Influence and the Power of Minorities: An Analysis of the Communist Manifesto, Social Justice Research, 17, 4, 357 – 388 |

| 5 | Silfwer, J. (2017, June 13). Conversion Theory — Disproportionate Minority Influence. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/conversion-theory/ |

| 6 | Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. |

| 7 | Rogers, E. (1976). New Product Adoption and Diffusion. Journal of Consumer Research, 2, 290 – 301. https://doi.org/10.1086/208642 |