What is a mind palace — and how do you use it?

In this article, I’ll share my learnings and insights from constructing a mind palace for myself.

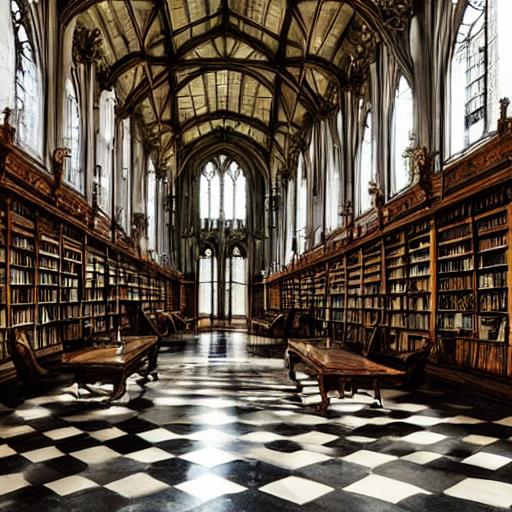

A mind palace (also known as a ‘memory palace’) is a mental construct of a metaphysical building with different imaginary “rooms.”

By adding a dimension of physicality to your mind, the idea is that you’ll be able to use your mind palace for memorisation (the Method of Loci) — but potentially also for other cognitive enhancements.

Here we go:

My Interest in Mind Palaces

Do you know those pop culture moments that stick — and stay with you? Here are a few such examples from my mind:

For me, such a seminal moment is from Sherlock, the British TV show starring Benedict Cumberbatch:

In the series, Sherlock Holmes and the villain Charles Augustus use a memory technique called the mind palace to commit information to memory. 1The television series Hannibal, starring Mads Mikkelsen as the genius psychopath with a peculiar taste for human flesh, also mentioned a mind palace. Weird eating habits and, more importantly, … Continue reading

The idea of having a mind palace appealed to me.

Is the mind palace a proper technique that one can use?

And if so, how does it work?

The Method of Loci

As it turns out, a mind palace isn’t just a television trope.

The mind palace is a mnemonic method used by ancient Greek and Roman scholars to commit large chunks of information to memory called the Method of Loci (loci = Latin for location). 2Method of loci. (2023, December 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Method_of_loci

Example:

Let’s say you want to memorise a deck of 52 cards. For this, you could think of a house with 13 (52 divided by 4) different rooms, rooms you pass through in a pre-decided order.

The first room is a hallway with a large antique mirror.

As you memorise the first playing card, let’s say an ace of hearts, you mentally attach the card to the mirror — and then you move on to the next room in your sequence.

You place 13 cards in 13 rooms attached to 13 different pieces of furniture. Then, you take the same route three more times, securing a new card for another piece of furniture in each room. Every room now contains four pieces of furniture with one unique playing card attached.

When you test how many of the 52 cards you remember, you enter the first room (the hallway), look at the first piece of furniture (the antique mirror), and find the ace of hearts.

“The design of a virtual memory palace significantly impacts memory performance, combining the loci method with modern technology for effective learning.”

Source: Technische Universität Braunschweig 3Huttner, J. (2021). Virtual Memory Palaces: The Impact of Design on the Memorization Performance. Technische Universität Braunschweig. https://doi.org/10.24355/DBBS.084 – 202102161019‑0

Our Brain’s Built-In GPS System

In 2014, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to John O’Keefe from University College London, May-Britt Moser, and Edvard Moser from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. 4The Nobel Assembly. (2014, October 6). The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2014. NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2014/press-release/

Scientists found that cells in our brain constitute a positioning system:

“… certain neurons in the hippocampus fired whenever a rat was in a certain place in the local environment, with neighbouring neurons firing at different locations, such that the entire environment was represented by the activity of these cells throughout the hippocampus.”

Source: Brainblogger.com 5Adaes, S. (2014, November 19). The Coordinates Of A Nobel Prize. Brainblogger.com. https://brainblogger.com/2014/11/19/the-coordinates-of-a-nobel-prize/

Assigning memory neurons to fire at specific locations is a clever way to conserve mental energy.

The mind palace technique makes good use of this brain feature; by assigning an imaginary (enhanced with other sensory information like the smell, sounds, temperature, lighting conditions, etc.) to a specific memory, recall becomes more accessible.

Mind Palaces in the Media

Here are a few examples of the memory palace or similar concepts being referenced in various forms of media:

Mind Places in Literature

Several examples of the memory palace concept or similar ideas appear in the literature. Some notable examples include:

These examples from literature illustrate how the memory palace concept has been explored in various ways, both as a historical practice and as a narrative device to explore the power and limits of human memory.

Altering Your Emotional States

In an online memory forum, I found ongoing discussions of what other uses there could be for having a mind palace:

One forum member used a mind palace to lower the heart rate before a nerve-wracking speech.

One forum member used a mind palace to sleep instead of counting sheep.

One forum member used a mind palace to prepare for meditation.

One forum member used a mind palace to increase focus in distracting environments.

One forum member used a mind palace to reinforce positive memories to combat depression and increase confidence.

Ergo: Some people have been using their mind palaces to alter or control their emotional states — with positive results.

To me, this sounds interesting and potentially useful.

Would it be possible to use a mind palace to improve cognitive control instead of practising raw memorisation techniques?

Techniques To Enhance Cognitive Abilities

A few years ago, I came across the creativity researcher Win Wenger. Wenger’s primary hypothesis was outlandish yet freakishly fantastic:

Since our subconscious speaks to us visually and not verbally, we can enhance our cognitive performance by reinforcing our inner image stream.

Here’s an interesting use case:

Imagine yourself sitting in a room with people that you look up to. It could be Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Stephen King. Discuss with them, and ask them questions. Visualise them as they speak.

Soon, your “avatar friends” might start to surprise you, contradict you, or even challenge you. Despite that, their words come from somewhere within yourself, of course.

From this example, we could imagine building a mind palace with several rooms filled with different types of valuable experts with one singular trait in common — they’re not you, even though they are.

The practice could bring the power of visualisation and location together, suggesting a powerful combination.

We could start seeing a “room” in a mind palace as a separate cognitive tool for purposes other than just committing information strings to memory.

Genius boardrooms. You could experiment with having imagined boardrooms inhabited by geniuses on standby for discussing decisions and solutions.

Mind Palace “Room” Examples

Of course, you can have rooms you like in your mind palace. Here are a few examples of rooms that I frequently use:

Meditation spots. Your mind palace could have rooms designed to strengthen the effects of your meditation practice.

Rehearsal rooms. Before giving a keynote or speech, I like to rehearse them mentally. I find that it helps me to rehearse my talks in a familiar space without distractions.

Memory library. I imagine a library where everything I ever learnt resides. Searching for the right book helps me retrieve lost memories. To commit something to memory, I think of going to the study hall and writing the information down in a book, then placing it somewhere specific in the library.

Gardens for walking and thinking. I think better when I’m walking. But if I can’t go for a walk, I can always go for a mental walk through one of many mind palace gardens.

Building a Mind Palace in Minecraft

For me, constructing the mind palace has been somewhat challenging. It requires focus and concentration for long periods. And life tends to get in the way.

Building a replica of my mind palace in Minecraft is helping reinforce my memories of its layout. As with Lego, I never forget a build. By building my mind palace in Minecraft, I’ve reinforced the metastructure in my mind.

This Minecraft trick has given my mental structure a form of stability. 6 I’m looking forward to VR and AR software dedicated to the use cases.

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

PR Resource: More Projects

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Improvement: Renaissance Projects

The Renaissance lasted from the 14th to the 17th century and was a period of significant cultural, artistic, political, and scientific rebirth in Europe.

Inspired by the Renaissance mindset, I strive to develop my creative intelligence, physical strengths, and mental well-being.

Better Identity

Better Thinking

Better Skills

Better Habits

Learn more: Creativity

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

PR Resource: More Better Thinking

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Doctor Spin’s PR School: Be Clear-Minded

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

Annotations

| 1 | The television series Hannibal, starring Mads Mikkelsen as the genius psychopath with a peculiar taste for human flesh, also mentioned a mind palace. Weird eating habits and, more importantly, fantastic memory techniques. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Method of loci. (2023, December 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Method_of_loci |

| 3 | Huttner, J. (2021). Virtual Memory Palaces: The Impact of Design on the Memorization Performance. Technische Universität Braunschweig. https://doi.org/10.24355/DBBS.084 – 202102161019‑0 |

| 4 | The Nobel Assembly. (2014, October 6). The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2014. NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2014/press-release/ |

| 5 | Adaes, S. (2014, November 19). The Coordinates Of A Nobel Prize. Brainblogger.com. https://brainblogger.com/2014/11/19/the-coordinates-of-a-nobel-prize/ |

| 6 | I’m looking forward to VR and AR software dedicated to the use cases. |