Are social media fakers becoming a severe issue?

In the wake of techlash, people are frustrated about social media fakers.

Many complain that ordinary people in their feeds are simply trying too hard. Many complain that influencers are too desperate for likes, clicks, and shares.

And amongst the complainers, I sense unconscious envy lurking in the shadows. We all crave attention and recognition, but most get none.

What’s going on?

Get Famous Online — Or Die Trying

Admit it. You follow someone on social media with a picture-perfect lifestyle but suspect they’re just faking it.

It used to be lifestyle influencers putting on a dazzling show for their followers, but now it’s your neighbour, co-worker, and old classmate.

“If you experience negative emotions, just unfollow them,” I say.

But it’s often not that simple. We live in an attention economy of likes where it isn’t easy to separate your online network from the physical world. The lines are blurred.

“People want to be loved; failing that admired; failing that feared; failing that hated and despised. They want to evoke some sort of sentiment. The soul shudders before oblivion and seeks connection at any price.”

— Hjalmar Söderberg (1869−1941), Swedish author

Read also: Online Wannabeism: Why We Mimic Social Media Influencers

Social Group Dynamics

Unfollowing someone, blocking someone, or even forgetting to like a friend’s Instagram picture may cause social discomfort. We get pulled into this world of social media fakers.

How did we end up here? And will we ever get out of it?

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Typical Social Group Sizes

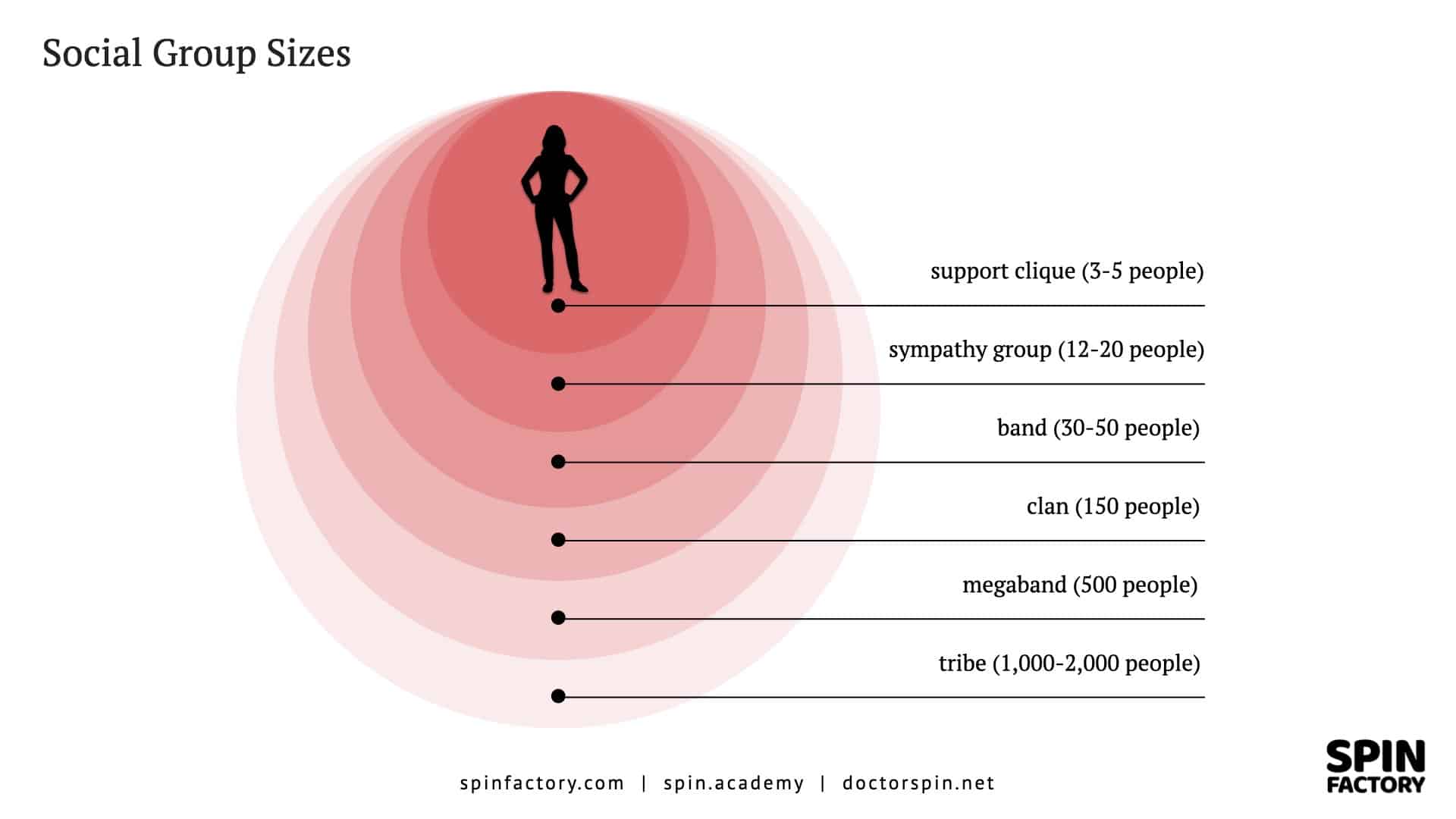

How many social connections you you comfortably sustain? According to the social brain hypothesis, limits exist. 1Zhou WX, Sornette D, Hill RA, Dunbar RI. Discrete hierarchical organization of social group sizes. Proc Biol Sci. 2005 Feb 22;272(1561):439 – 44.

“The ‘social brain hypothesis’ for the evolution of large brains in primates has led to evidence for the coevolution of neocortical size and social group sizes, suggesting that there is a cognitive constraint on group size that depends, in some way, on the volume of neural material available for processing and synthesizing information on social relationships.”

Source: Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2Zhou, X., Sornette, D., Hill, R. A., & M. Dunbar, R. I. (2005). Discrete hierarchical organization of social group sizes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272(1561), … Continue reading

Scientific evidence suggests that people tend to organise themselves not in an even distribution of group sizes but in discrete hierarchical social groups of more particular sizes:

Alas, there seems to be a discrete statistical order in the complex chaos of human relationships:

“Such discrete scale invariance could be related to that identified in signatures of herding behaviour in financial markets and might reflect a hierarchical processing of social nearness by human brains.“

Source: Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 3Zhou, X., Sornette, D., Hill, R. A., & M. Dunbar, R. I. (2005). Discrete hierarchical organization of social group sizes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272(1561), … Continue reading

Read also: Group Sizes (The Social Brain Hypothesis)

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR ideas.

The First “Reality Stars”

In 1997, the Swedish public service broadcaster SVT launched Expedition Robinson; a reality television show spun off the British format Survivor.

A group of chosen not-yet-celebs participated in a contest set on a Malaysian island. One after the other, people got voted off the show.

The Swedish mainstream audience devoured the show, partly because of the palm trees and the beaches but mainly because “ordinary people” were running around half-naked with low blood sugar.

In the dark of a long Swedish winter, the show was exotic.

And it became a media phenomenon.

A fierce love-and-hate relationship with these new reality stars emerged. The audience genuinely loved some characters just as much as they hated others. And that passionate engagement caused severe issues for those reality stars who failed to become loved. 4The situation worsened as the first person to be voted off the island, Sinisa Savija, committed suicide, forcing SVT and the production company to re-cut the rest of the programs to lessen the … Continue reading

Many early “reality stars” found the public hate so unbearable they lashed out against the production company:

“I’m a human being with many sides,” they cried. “Why portray me as a monster?”

The First Class of Professional Social Media Fakers

Fast forward from 1997 to 2016.

Today, reality stars understand how the game is supposed to be played. They want to be edited as dramatic characters.

Internationally, the Kardashian family must be considered the reigning masters of massive social media spin. Authenticity is less critical than making the performance feel authentic. It’s the online equivalent of “suspension of disbelief.”

In Sweden, we still turn to reality television shows like Paradise Hotel. Because they put on a show, participants quickly acquire substantial social media followings and tons of tabloid attention.

The new breed of reality stars understands that they must deliver drama and that the format doesn’t exist to serve their multi-faceted need for human expression. The unspoken agreement is straightforward: treat the audience to a show, and they’ll grant you stardom.

In other words: It’s social media show business.

Today, the mainstream audience understands the reality of reality television. But we’re not there yet when it comes to social media.

New Media Adoption Takes Decades

How long did it take for the mainstream audience to fully accept reality television’s media logic?

By my count, the process in Sweden took 19 years (1997 – 2016). That’s nearly two decades to grow accustomed to a specific media phenomenon (that never was a secret).

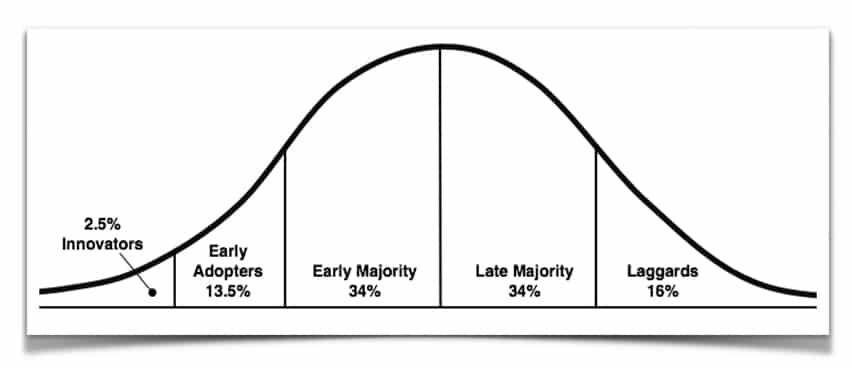

The process follows the principles as outlined in the law of diffusion of innovation:

Compared to reality television, social media is far more complex. And it has changed the fabric of human interconnection in a way that reality television never did.

How long will it take the mainstream audience to come to terms with the inherent media logic of social media?

Will two decades suffice? Or will digital media keep progressing and never allow us to catch up?

“In Real Life” and Reality

In the early days of the Hippie Web (2005 – 2015), IRL — In Real Life— became a popular expression. It accentuated the distinction between online realities and the physical world.

But as early as 2006 – 2007, many began to question the IRL expression. “Our online lives are as real as our physical reality, so we should talk about AFK — Away From Keyboard — instead.”

Unfortunately, they were wrong.

Social media is many things, but unequivocally real isn’t one of them. It only feels real.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with only showcasing one particular side of something. It’s not wrong to entertain an audience. It’s not wrong to tell incredible stories and to create cultural expressions through art.

But we’re all still learning how to deal with social media.

We still have tons of social media issues to manage.

We’re not all social media naturals yet.

It took two decades for the mainstream audience to learn that reality television isn’t real. And it will probably take the mainstream audience at least two decades to learn that social media isn’t real — probably longer.

Social Media Fakers and Online Wannabeism

If you want to show off the parts of your life that are beautiful and picture-perfect, then by all means — go ahead. If you want to put on a show for your followers, it’s your prerogative.

But we would all be wise to remember that social media isn’t real:

Social media fakeness can cause stress and mental health problems for both the content creator and the follower.

Read also: “I’m Quitting Social Media”

There have been many conversations lately about the “fakeness” of social media. One example is how Essena O’Neill, a young Australian Instagram influencer, publicly ranted about her (and everybody else’s) fakeness on social media. “I quit,” she said and deleted her Instagram and YouTube accounts — only to use the extra attention to launch her next online enterprise.

Read also: Essena O’Neill and the Show Business of Social Media

If nothing else, we should remember that social media has existed for two decades. We might be at the tail end of the adoption curve. While not everyone has been caught up, more people are coming to terms with today’s media logic.

Beware of Social Media Desperation

Younger generations are already calling out “boomers,” “simps,” and “weird flex.” “Cringe” might be on sale, but they’re not buying.

Today, we must expect a significant portion of the audience to be asking cynical questions like:

A word of caution:

Anyone too thirsty for attention and validation through social media risks becoming a pariah. Instead of promoting an élite class, the mainstream might equate desperation with weakness and shove them to the bottom of the status ladder.

“A status update with no likes (or a clever tweet without retweets) becomes the equivalent of a joke met with silence. It must be rethought and rewritten. And so we don’t show our true selves online, but a mask designed to conform to the opinions of those around us.”

— Neil Strauss, Wall Street Journal

Thanks for reading. Please support my blog by sharing articles with other communications and marketing professionals. You might also consider my PR services or speaking engagements.

PR Resource: Social Media Sharing

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Why We Share on Social Media

“People want to be loved; failing that admired; failing that feared; failing that hated and despised. They want to evoke some sort of sentiment. The soul shudders before oblivion and seeks connection at any price.”

— Hjalmar Söderberg (1869−1941), Swedish author

When we share on social media, we share for a reason. And that reason typically has something to do with ourselves:

If you can get social media to work for you, great. But you should also be mindful not to let the pressure get the better of you.

“A status update with no likes (or a clever tweet without retweets) becomes the equivalent of a joke met with silence. It must be rethought and rewritten. And so we don’t show our true selves online, but a mask designed to conform to the opinions of those around us.”

— Neil Strauss, Wall Street Journal

Learn more: The Narcissistic Principle: Why We Share on Social Media

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR ideas.

PR Resource: Social Media Logic

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Social Media Logic

Media logic is a set of theories describing how the medium affects the media. Typically, the format (as the medium dictates) influences the mediated message.

“Media logic is defined as a form of communication, and the process through which media transmit and communicate information. The logic and guidelines become taken for granted, often institutionalized, and inform social interaction. A basic principle is that media, information technologies, and communication formats can affect events and social activities.“

Source: The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication 5Altheide, D. L. (2016). Media Logic. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication, 1 – 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc088

As famously stipulated by Marshall McLuhan, “The medium is the message.” What are the typical media logic effects on mediated messages?

Classic Media Logic Effects

Media logic is hypothesised to influence the news media in the following ways: 6Nord, L., & Strömbäck, J. (2002, January). Tio dagar som skakade världen. En studie av mediernas beskrivningar av terrorattackerna mot USA och kriget i Afghanistan hösten 2001. … Continue reading

The effects of the above media logic can also be recognised in social media. Still, social network algorithms seem to add even more effects:

Social Media Logic Effects

“Social media logic, rooted in programmability, popularity, connectivity, and datafication, is increasingly entangled with mass media logic, impacting various areas of public life.”

Source: Writing Technologies eJournal 7Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding Social Media Logic. Writing Technologies eJournal. https://doi.org/10.17645/MAC.V1I1.70

Based on the suggested additions for social platforms, we can add four extra dimensions to the classic media logic effects model:

Social media logic seems entangled with classic media logic. While more complex, social networks seem to amplify the effects of classic media logic.

Learn more: Social Media Logic: The Amplification of Media Effects

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR ideas.

PR Resource: Seeking Attention

“There’s only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

— Oscar Wilde

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

The Anatomy of Attention

Attention is an essential component of public relations:

And it’s not just organisations. We all seem to crave attention in some form or another:

“People want to be loved; failing that admired; failing that feared; failing that hated and despised. They want to evoke some sort of sentiment. The soul shudders before oblivion and seeks connection at any price.”

— Hjalmar Söderberg (1869−1941), Swedish author

It’s fear of social isolation— and attention starvation.

But what constitutes ‘attention’?

“Attention is a complex, real neural architecture (‘RNA’) model that integrates various cognitive models and brain centers to perform tasks like visual search.”

Source: Trends in cognitive sciences 8Shipp, S. (2004). The brain circuitry of attention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 223 – 230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.03.004

Each of the below terms refers to a specific aspect or type of attention (“mental bandwidth”), a complex cognitive process. 9Schweizer, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Goldhammer, F. (2005). The structure of the relationship between attention and intelligence. Intelligence, 33(6), 589 – 611. … Continue reading

Let’s explore different types of attention:

Each type of attention plays a crucial role in how we interact with and process information from our environment, and understanding these different aspects is key in fields like psychology, neuroscience, and education.

Learn more: The Anatomy of Attention

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR ideas.

ANNOTATIONS

| 1 | Zhou WX, Sornette D, Hill RA, Dunbar RI. Discrete hierarchical organization of social group sizes. Proc Biol Sci. 2005 Feb 22;272(1561):439 – 44. |

|---|---|

| 2, 3 | Zhou, X., Sornette, D., Hill, R. A., & M. Dunbar, R. I. (2005). Discrete hierarchical organization of social group sizes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272(1561), 439 – 444. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.2970 |

| 4 | The situation worsened as the first person to be voted off the island, Sinisa Savija, committed suicide, forcing SVT and the production company to re-cut the rest of the programs to lessen the drama. |

| 5 | Altheide, D. L. (2016). Media Logic. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication, 1 – 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc088 |

| 6 | Nord, L., & Strömbäck, J. (2002, January). Tio dagar som skakade världen. En studie av mediernas beskrivningar av terrorattackerna mot USA och kriget i Afghanistan hösten 2001. ResearchGate; Styrelsen för psykologiskt försvar. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271014624_Tio_dagar_som_skakade_varlden_En_studie_av_mediernas_beskrivningar_av_terrorattackerna_mot_USA_och_kriget_i_Afghanistan_hosten_2001 |

| 7 | Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding Social Media Logic. Writing Technologies eJournal. https://doi.org/10.17645/MAC.V1I1.70 |

| 8 | Shipp, S. (2004). The brain circuitry of attention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 223 – 230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.03.004 |

| 9 | Schweizer, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Goldhammer, F. (2005). The structure of the relationship between attention and intelligence. Intelligence, 33(6), 589 – 611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2005.07.001 |