We all know how social media algorithms work, right?

Most people think they know how social media algorithms work, but they don’t. This article will shed some light on how algorithms use iterative testing — not sophisticated technology.

As a digital strategist, I’ve closely monitored social media algorithms for two decades. I’ve learnt that algorithms aren’t your friends — and we must manage them.

Here we go:

We Need Sorting and Labelling

You interact with social media, and the platform owner collects your user data to serve you more content to keep you engaged and thus increase your exposure to third-party advertising.

Order is necessary, of course, since there’s a lot of content to structure:

Unfortunately, the actual inner workings of a social media algorithm have a much darker side. And yes, “darkness” is a reasonable analogy because these algorithms are being kept secret for many reasons.

Behind these curtains of secrecy, we don’t find myriads of complex computing layers but manufactured filters designed by real people with personal agendas.

We are constantly shaping, suggesting, nudging, and presenting.

Social Algorithms are Not “Personal”

As users, we have a general idea of how algorithms work, but only a handful of people know. To prevent industrial espionage, we can safely assume that most social networks are making sure that no one developer has full access to the entirety of an algorithm.

And even if you’re a Facebook programmer, how would you know exactly how Google’s algorithm works?

One might assume you have a personal Facebook algorithm stored on a server somewhere. An algorithm that tracks you personally and learns about you and your behaviour. And the more it knows about you, the better it understands you. But this is not exactly how it works — for a good reason.

Humans are notoriously bad at consciously knowing ourselves and understanding others. And our thinking is riddled with unconscious biases.

However complex, applying various types of machine learning to learn about users and their interactions on the individual level would be both slow and expensive. Few social media users would be patient enough to endure such a lengthy process through trial and error.

Anyone familiar with data mining will know that more advanced scraping techniques, like sentiment analysis from social media monitoring, will require large data sets. Hence, the term “big data.” 1Batrinca, B., Treleaven, P. Social media analytics: a survey of techniques, tools and platforms. AI & Soc, 89 – 116 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-014‑0549‑4

A social media algorithm gets immense power primarily from harvesting data from large users simultaneously and over time, not from creating billions of self-contained algorithms.

Put another way: Algorithms are figuring out humanity at scale, not your behaviour.

Our Lack of Consistency

No one argues the fact that you are an individual. But is your behaviour consistent from interaction to interaction? The answer is probably no. How you act and react will likely be much more contextual and situational — at least concerning your perceived uniqueness and self-identification.

Social networks are limiting your options to tweak “your algorithm” yourself. I would be all over the possibility of adjusting Facebook’s newsfeed or Google’s search results in fine detail using various boolean rulesets. However, that would probably only teach the master social algorithm more about human pretensions — and little else.

Accurate personal algorithms that follow us from service to service could outperform all other algorithms. I would probably ask my algorithm only to show me serious articles written in peer-reviewed publications or published by well-educated authors with proven track records. But if the algorithm doesn’t take it upon itself to show me some funny cat memes or weird YouTube clips now and then, I would probably be bored quite quickly.

When we understand that the social media algorithms aren’t trying to figure you out, it follows to ask how well they’re doing in figuring out humanity.

Why Social Media Algorithms Aren’t Better

Social media algorithms are progressing — painstakingly. Understanding human behaviour at the macro level is not a task to be underestimated.

The practical approach to these struggles is straightforward:

Eliminate the guesswork.

The Silent Switch

All social media algorithms are built differently and are constantly being developed. At the same time, social media users’ behaviours are evolving.

Still, there was a way that social media algorithms used to behave—and there is a way that social media algorithms behave now.

This has been a fundamental but silent switch.

How Social Media Algorithms Used To Behave

For more than a decade, social media algorithms would deliver organic reach according to a distribution that looked something like this:

This distribution of organic reach enabled organisations to use social media despite not being “media companies.”

How Social Media Algorithms Behave Today

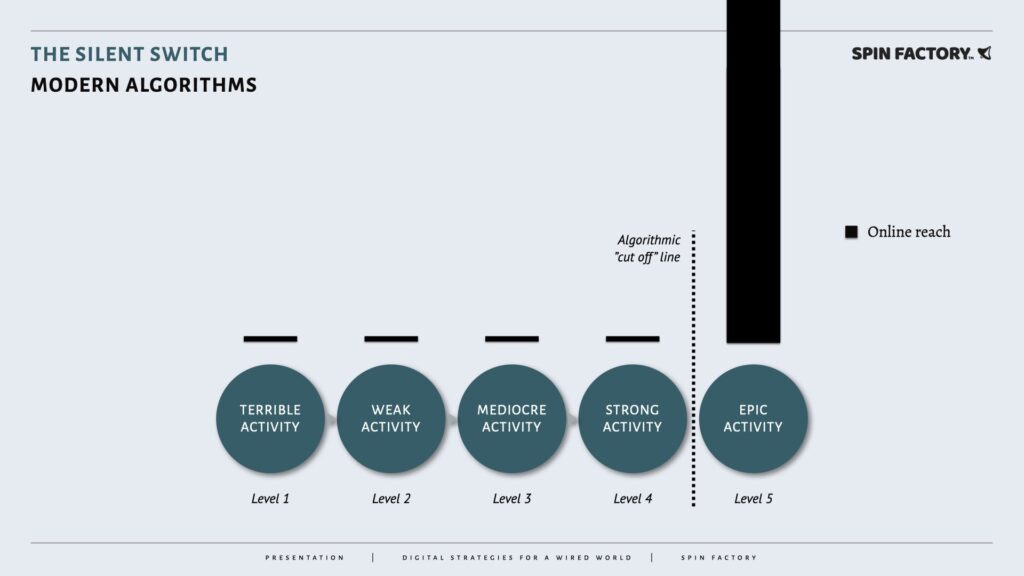

Today, after the silent shift, social media algorithms deliver organic reach more like this:

The increased competition and sophistication among content creators partially explain this new type of distribution. However, going viral is still just as possible for anyone.

How does this work?

The Single Content Algorithm

How can a social network predict what users will like?

Content from a trusted creator trusted by a large community of followers used to be the leading indicator of future performance. But today, social networks have found a better way to predict content success.

The single content algorithm = when social networks demote content creator authority to promote single content performance to maximise user engagement for ad revenue.

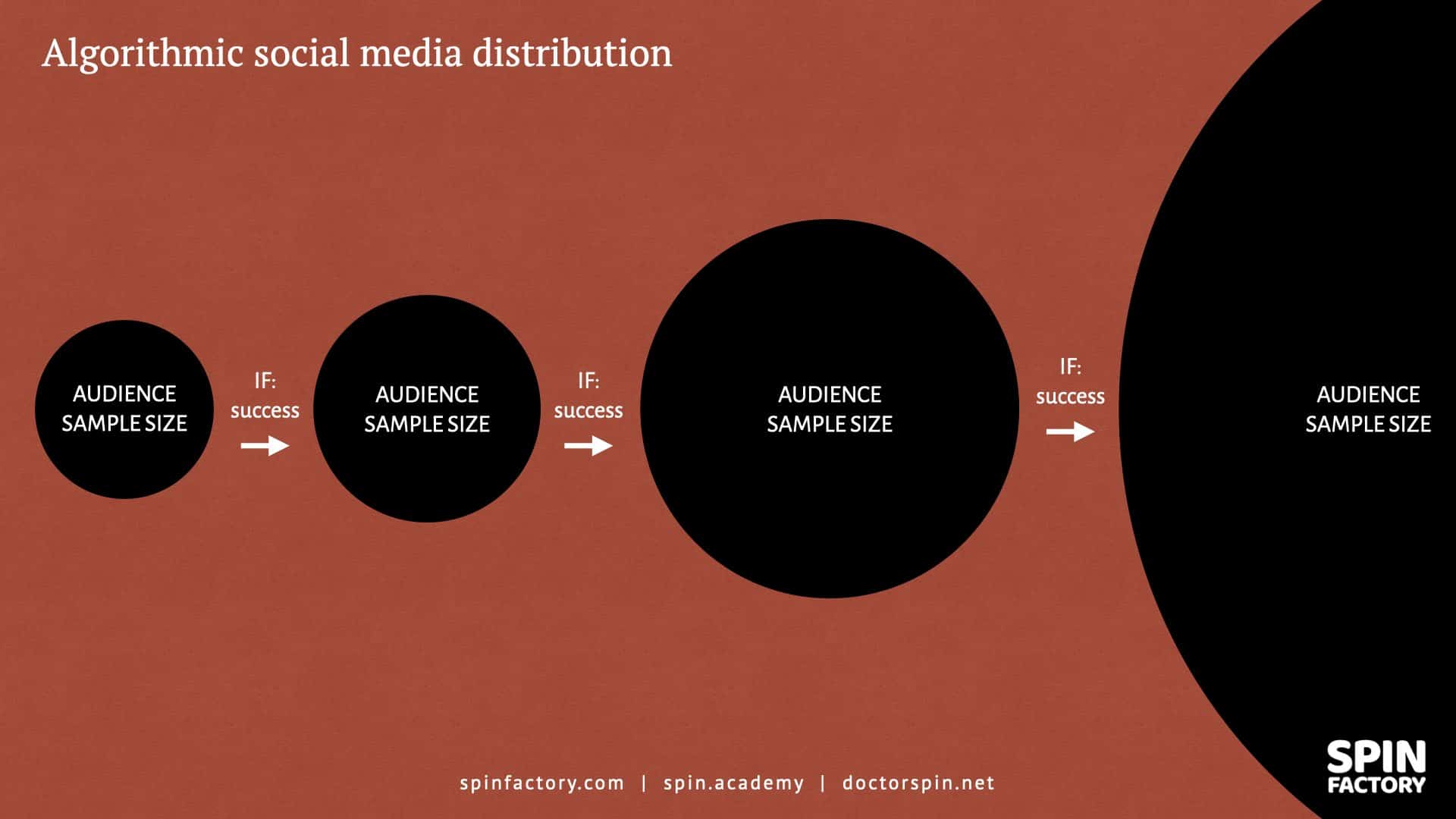

The single content algorithm presents newly published content to a limited audience sample size:

If the newly published content tests successfully, the social media algorithm pushes that content to a slightly larger statistical subset. And so on.

This iterative process means that single pieces of content worthy of going viral will go viral, a) even if it takes a longer time, and b) regardless of the content creator’s number of followers.

Learn more: The Silent Switch

Virality Through Real-Time Testing

A dominating feature of today’s social media algorithms is real-time testing.

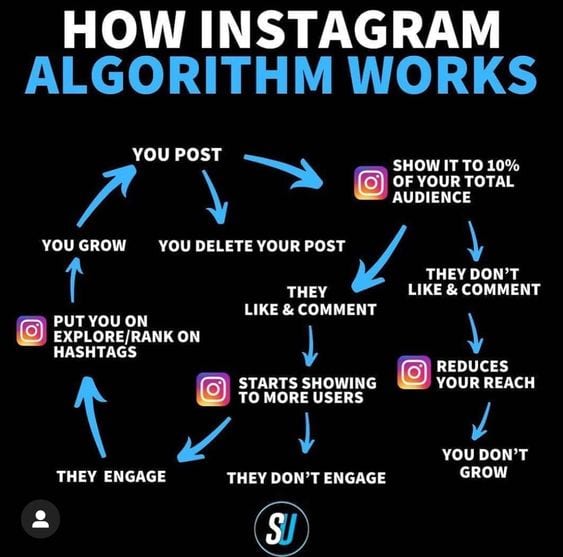

If you publish anything, the algorithm will use its data to test your content on a small statistical subset of users. If their reactions are favourable, the algorithm will show your published content to a slightly larger subset — and then test again. And so on.

Suppose your published content has viral potential, and your track record as a publisher has granted you enough platform authority to surpass critical mass. In that case, your content will spread like rings on water throughout more extensive subsets of users.

This testing algorithm isn’t as mathematically complex as one might think from a programming standpoint. The most robust approach to increasing virality is reducing cycle times.

YouTube’s algorithm arguably does well in cycle times, but the real star of online virality is the Chinese platform TikTok.

Read also: What You Need To Know About TikTok’s Algorithm

And this is where it gets pitch black. The complexity and gatekeeping prowess of today’s social media algorithms don’t primarily stem from their creative use of big data and high-end artificial intelligence but from the blunt use of synthetic filters.

The social media algorithms could be much more complex using machine learning, natural language processing, and artificial intelligence combined with human psychology neural network models. Especially if we allow these protocols to be individual across services, we will enable them to lie to us just a bit.

But, no. Instead, the social media algorithms of today are surprisingly straightforward and based on real-time iterative testing. Today, virality is controlled mainly via the use of added filters.

Underestimating the Effects of Filters

The algorithmic complexity is primarily derived from humans manually adding filters to algorithms in their control. These filters are tested on smaller subsets before rolling out on larger scales.

Most of us have heard creators on Instagram, TikTok, and sometimes YouTube complain about being “shadowbanned” when their reach suddenly dwindles from one day to the next — for no apparent reason. Sometimes, this might be due to changes to the master algorithm, but most creators are probably affected by newly added filters.

Please make no mistake about it: Filters are powerful. No matter how well a piece of content would negotiate the master algorithm — if a piece of content gets stuck in a filter, it’s going nowhere. And these filters aren’t the output of some ultra-smart algorithm; humans add them with corporate or ideological agendas.

“There is no information overload, only filter failure.”

— Clay Shirky

TikTok serves as one of the darkest examples of algorithmic abuse.

Leaked internal documents revealed how TikTok added filters to limit content by people classified as non-attractive or poor.

And yes, this is where the darkness comes into full effect — when human agendas get added into the algorithmic mix.

“One document goes so far as to instruct moderators to scan uploads for cracked walls and “disreputable decorations” in users’ own homes — then to effectively punish these poorer TikTok users by artificially narrowing their audiences.”

Source: The Intercept 2Biddle, S., Paulo Victor Ribeiro, & Dias, T. (2020, March 16). TikTok Told Moderators to Suppress Posts by “Ugly” People and the Poor to Attract New Users. The Intercept. … Continue reading

The grim irony is that adding filters is relatively straightforward from a programming perspective.

We often consider algorithms advanced black boxes that operate almost above human comprehension. However, with reasonably exact algorithms, it is artificial filters we need to watch out for and consider.

Enter: The Electronic Age

Human culture is often described based on our access to production technologies (e.g., the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age).

According to Marshall McLuhan and the Toronto School of Communication Theory, a better analysis would be to view societal development based on the prominence of emerging communications technologies.

McLuhan’s Four Epochs

McLuhan suggests dividing human civilisation into four epochs:

“The Gutenberg Galaxy is a landmark book that introduced the concept of the global village and established Marshall McLuhan as the original ‘media guru’, with more than 200,000 copies in print.”

Source: Modern Language Review 3McLuhan, M. (1963). The Gutenberg galaxy: the making of typographic man. Modern Language Review, 58, 542. https://doi.org/10.2307/3719923

As a PR professional and linguist, I subscribe to the concept of the Electronic Age. I firmly believe society is unlikely to revert to the Gutenberg Galaxy.

Like the rest of society, the PR industry must commit to digital-first, too. Mark my words: It’s all-in or bust.

Read also: The Electronic Age and the End of the Gutenberg Galaxy

The Power of Perception Management

This is the truth about how social media algorithms are controlling our lives:

No one makes decisions based on actual reality; we all make decisions based on our limited mental maps (i.e. sensory “bits and pieces” stitched together of that reality). Hence, if you control some parts of people’s perceptions, you indirectly control what people do, say, or even think. 4Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan.

Social media algorithms influence our mental maps of reality and, by extension, our attitudes and behaviours.

What would happen if Google and Facebook filtered away a specific day? Everything that refers to that day wouldn’t pass any iterative tests anymore. Any content from that day would be shadowbanned. And search engine results pages would deflect anything related to that particular day.

“Since we cannot change reality, let us change the eyes which see reality.”

— Nikos Kazantzakis

To paraphrase a popular TikTok meme, “How would you know?”

Learn more: Walter Lippmann: Public Opinion and Perception Management

The First Rule of Social Media Algorithms

Social networks don’t want us talking and asking questions about their algorithms despite being at the core of their businesses. Because 1) they need to keep them secret, 2) they are blunter than we might think, 3) their complexity is manifested primarily by artificial filters, and 4) they don’t want to direct our attention at how much gatekeeping power they yield.

And both journalists and legislators aren’t exactly hard at exposing these apparent democratic weaknesses; journalists want their lost gatekeeping power back and legislators because they see ideological opportunities to gain control over these filters.

Any PR professional knows that the news media has an agenda. And that we must manage that agenda. Otherwise, it might spin out of control.

A social media algorithm can be successfully negotiated and sometimes work for you or your organisation. But an algorithm with its filters will never be your friend.

Social networks are “good” in the same way the news media is “objective”, or politicians are “altruistic”. As public relations professionals, we should act accordingly and manage the social media algorithms — just as we manage journalists and legislators.

Read also: Social Media: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

PR Resource: More Social Media

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Spin’s PR School: Free Social Media PR Course

Discover this free Social Media PR Course and master the art of digital public relations on social networks and platforms. Explore now for valuable insights!

Social Media Psychology

Social Media Management

Social Media Issues

Learn more: All Free PR Courses

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

PR Resource: The 7 Graphs of Algorithms

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Types of Algorithm Graphs

Search engines, social networks, and online services typically have a wealth of user data to optimise the user experience.

Here are examples of different types of graphs that social media algorithms use to shape desired behaviours:

The different graphs are typically weighted differently. For instance, some media companies allow a fair degree of social graph content, while others offer almost none. Changes are constantly being enforced, and the silent switch might be the most notable example of a media company shifting away from the social graph. 5Silfwer, J. (2021, December 7). The Silent Switch — A Stealthy Death for the Social Graph. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/silent-switch/

The media company can leverage these graphs using two main approaches:

Today, profiling seems to be the dominant approach amongst media companies.

Learn more: The 7 Graphs of Algorithms: You’re Not Unknown

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

Annotations

| 1 | Batrinca, B., Treleaven, P. Social media analytics: a survey of techniques, tools and platforms. AI & Soc, 89 – 116 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-014‑0549‑4 |

|---|---|

| 2 | Biddle, S., Paulo Victor Ribeiro, & Dias, T. (2020, March 16). TikTok Told Moderators to Suppress Posts by “Ugly” People and the Poor to Attract New Users. The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2020/03/16/tiktok-app-moderators-users-discrimination/ |

| 3 | McLuhan, M. (1963). The Gutenberg galaxy: the making of typographic man. Modern Language Review, 58, 542. https://doi.org/10.2307/3719923 |

| 4 | Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan. |

| 5 | Silfwer, J. (2021, December 7). The Silent Switch — A Stealthy Death for the Social Graph. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/silent-switch/ |

Social Media Mechanics