Are we starting to mimic social media influencers?

I’m a digital PR expert, but I’m also a regular social media user. I follow friends, family, and acquaintances on my social media accounts. But something seems to be … off.

Often, average social media users seem to mimic influencer mannerisms — despite having no audience other than family and friends.

What’s going on?

In this blog post, I’ll discuss a form of online wannabeism; how regular people in your feeds are suddenly starting to talk and act like influencers — despite having no real audiences to address.

Here we go:

Online Wannabeism

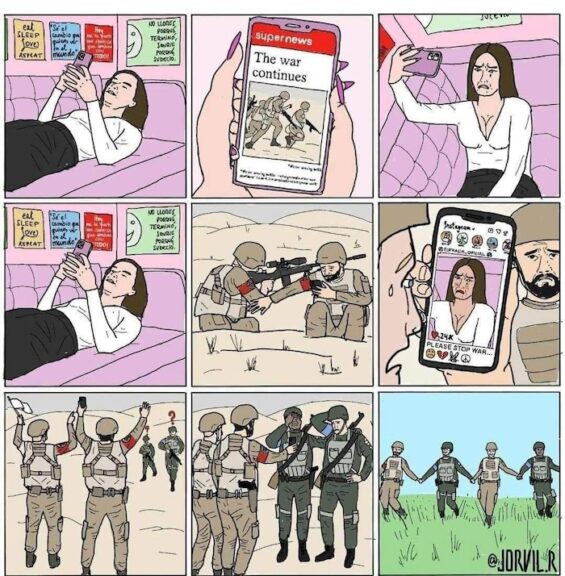

We might not all be influencers, but that doesn’t stop us from mimicking their behaviours when we create and publish content.

The widespread behaviour where non-influencers mimic influencer mannerisms is fascinating — and somewhat sad.

Online wannabeism = when a regular social media user mimics influencer mannerisms while creating content; a form of aspirational roleplay in front of an imagined audience. 1Silfwer, J. (2021, August 10). Online Wannabeism: Why We Mimic Social Media Influencers. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/online-wannabeism/

The Social Mirror Theory

Where does this online wannabeism stem from?

The social mirror theory is a psychological concept that suggests that people learn to see themselves and their identities through how others react to them. The theory suggests that people use the reactions of others as a “mirror” to understand and form their sense of self.

The theory posits that our sense of self is shaped by how we believe others perceive us. Rather than forming identity in isolation, we construct it by internalising social feedback — seeing ourselves reflected through the “mirror” of others’ reactions, judgments, and expectations.

The social mirror theory suggests that “[…] people are incapable of self-reflection without considering a peer’s interpretation of the experience. In other words, people define and resolve their internal musings through other’s viewpoint.” 2Social mirror theory. (2023, July 21). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_mirror_theory

Influencers as Peer Mirrors

Today, our “peer mirrors” have become fragmented and populated by online influencers, often exaggerating performative validation.

A study published in 2017 found that influencer content significantly shapes consumers’ attitudes, which then positively influences behaviour by triggering their underlying desire to imitate social media influencers. 3Lim, X. J., Radzol, A. M., Cheah, J.-H., & Wong, M. W. (2017). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Computers in Human … Continue reading

Naturally, influencers can’t sustain numerous simultaneous two-way relationships on equal terms with their audience. So, these relationships must be one-sided in nature.

The audience can only mimic their favourite online “peers” to feel closer to them.

“The main-test results, using the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis via AMOS 23, confirmed that the conceptual model and all the hypothesised relationships were statistically significant. Further, the bootstrap results demonstrated that a target’s mimicry desire indeed served as a significant mediator linking the target’s attitudinal beliefs to behavioural decisions.”

Source: University of Tennessee 4Ki, C. (2018, March). The Drivers and Impacts of Social Media Influencers: The Role of Mimicry. University of Tennessee. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/268799921.pdf

Learn more: Online Wannabeism: Why We Mimic Social Media Influencers

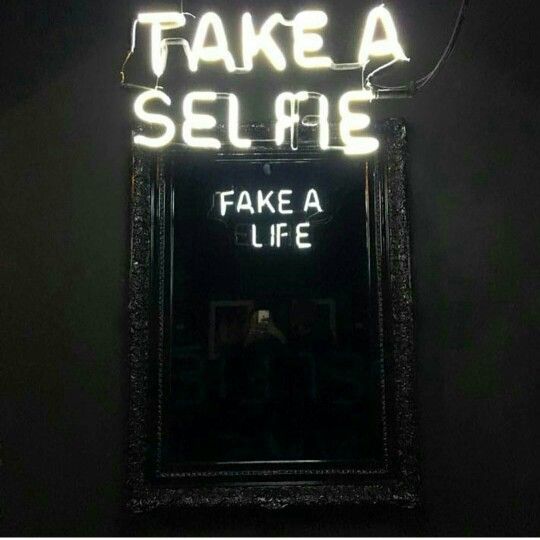

The Selfie Generation

I turned 30 in 2009 and spent the following decade experiencing a social media universe dominated by teens and 20-somethings.

Sure, new trends are exciting, but still.

I love social media—just not all of it.

Welcome to the internet.

I could do without motivational quotes, bathroom selfies, impossible ping-pong trick shots, wingtip sunsets, Instagram teen models, jet-set lifestyles with filter packs, keeping up with reality superstars, LinkedIn networking threads, Tik Tok pranks, butt posing in yoga pants, baby pictures, MrBeast, Twitch streamers speaking in baby voices, man-buns making perfect cups of coffee, rampant Twitter debates, and snapshots of feet on beaches.

I’ve since loathed seeing otherwise mature, intelligent, middle-aged friends do duckface selfies in front of their bathroom mirrors — or weirdly flexing about their latest triathlon training session. 5Silfwer, J. (2021, August 10). Online Wannabeism. Doctor Spin | the PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/online-wannabeism/

A Generation of Kidults

We’re a generation of adults who don’t know what it means to be grownups on social media. We’re “kidults.”

“Being young today is no longer a transitory stage, but rather a life choice, well established and brutally promoted by the media system. While the classic paradigms of adulthood and maturation could interpret such infantile behavior as a symptom of deviance, such behavior has become a model to follow, an ideal of fun and being carefree, present in a wide variety of contexts of society. The contemporary adult follows a sort of thoughtful immaturity, a conscious escape from the responsibilities of an anachronistic model of life. If an ideal of maturity remains, it does not find behavioral compensations in a society where childish attitudes and adolescent life models are constantly promoted by the media and tolerated by institutions.”

Source: ResearchGate 6Bernardini, J. (2014, June 30). The Infantilization of the Postmodern Adult and the Figure of Kidult. ResearchGate. … Continue reading

Some take the route of being omnipotent multi-experts who are fiercely opinionated about everything. Others try to save the world by organising themselves around the central task of shaming others publicly. Some try too hard to impress others by self-promoting their personal life choices. 7Silfwer, J. (2022, September 6). Social Media — The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/social-media/

Others opt out. Some of us censor ourselves in fear of social isolation, opinion corridors, and mighty echo chambers. 8Silfwer, J. (2023, December 15). Echo Chambers: Algorithmic Confirmation Bias. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/echo-chambers/ 9Silfwer, J. (2020, June 4). The Spiral of Silence. Doctor Spin | the PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/spiral-of-silence/

“To me, it’s just one symptom of a broader trend of infantilisation in Western culture. It began before the advent of smartphones and social media. But, as I argue in my book “The Terminal Self,” our everyday interactions with these computer technologies have accelerated and normalised our culture’s infantile tendencies.”

— Simon Gottschalk, professor of Sociology at the University of Nevada

How To Be a Grownup on Social Media

We resort to clickbait, humble bragging, and virtue signalling in our desperate search for likes. 10Silfwer, J. (2023, November 22). The Anatomy of Attention. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/attention/

To me, it all seems… lonely.

“A status update with no likes (or a clever tweet without retweets) becomes the equivalent of a joke met with silence. It must be rethought and rewritten. And so we don’t show our true selves online, but a mask designed to conform to the opinions of those around us.”

— Neil Strauss, Wall Street Journal

But it’s never too late to be a grownup on social media:

But First, Let Me Take a Selfie

I think of social media behaviours as I ponder the varying levels of emotional maturity among my peers in the selfie generation. I feel sorry for us.

Getting sucked into a maelstrom of clickbait and humblebrags is mentally taxing.

Imagine if we, at least those who consider ourselves adults and wish to opt out of the selfie generation, could shift our approach to social media. Wouldn’t that be something?

Sounds great, I think.

But first, let me take a selfie.

Learn more: The Selfie Generation

Emotional Maturity and Social Media

How do we better understand the emotional maturity of the selfie generation? In The Secret of Maturity by Kevin Everett FitzMaurice, a maturity progression of six steps is outlined:

Level 1: Emotional Responsibility

Level 1 maturity means that you understand that your feelings are your choices. People who haven’t yet reached this level of maturity tend to blame their feelings on external stimuli, such as other people, places, things, forces, fate, and spirits.

Lacking emotional responsibility on social media: When people get easily offended, especially on behalf of others.

Level 2: Emotional Honesty

Level 2 maturity means understanding your feelings and having the coping mechanisms to allow genuine emotions instead of suppressing them. People who have yet to reach this level of maturity tend to hurt themselves emotionally because they have yet to learn how to cope with their inner emotions.

Lacking emotional honesty on social media: When people publicly paint themselves as victims of their feelings.

Level 3: Emotional Openness

Level 3 maturity means that you can be purposeful in venting your emotions with the intent to let them go because you’re done with them. People who haven’t yet reached this level of maturity tend to be insecure in knowing how and when to share their feelings.

Lacking emotional openness on social media: When people publicly overshare to wallow or are unaware that their sharing has the opposite effect than they were aiming for.

Level 4: Emotional Assertiveness

Level 4 maturity means that you take responsibility for clearly communicating your emotional needs with those who care about you. People who have yet to reach this maturity level tend to fear asking others to respect their emotional needs.

Lacking emotional assertiveness on social media: When people allow others to make them feel bad but cannot set whatever boundaries they need.

Level 5: Emotional Understanding

Level 5 maturity means you no longer force yourself into imaginary or convenient ideas about who you are and what you should feel. People who haven’t yet reached this level of maturity tend to have certain firm beliefs about themselves that stem from ideas or principles, not genuine emotions.

Lacking emotional understanding on social media: When people try too hard to virtue signal and project a false self-image, they only make themselves feel worse.

Level 6: Emotional Detachment

Level 6 maturity means you are detached from your ego, and nothing can no longer bother you beyond your control. People who haven’t yet reached this level of maturity tend to have certain self-concepts to defend or promote.

Lacking emotional detachment on social media: When people can’t truly appreciate living in a world where people make each other feel good and bad about things.

Learn more: Emotional Maturity and Social Media

The Anatomy of Attention

Attention is an essential component of public relations:

An organisation, starved of attention, trust, and loyalty, is compelled to wage a perpetual struggle for its continued existence.

And it’s not just organisations. We all seem to crave attention in some form or another:

“People want to be loved; failing that admired; failing that feared; failing that hated and despised. They want to evoke some sort of sentiment. The soul shudders before oblivion and seeks connection at any price.”

— Hjalmar Söderberg (1869−1941), Swedish author

It’s fear of social isolation—and attention starvation.

“There’s only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

— Oscar Wilde

Types of Attention

But what constitutes ‘attention’?

“Attention is a complex, real neural architecture (‘RNA’) model that integrates various cognitive models and brain centers to perform tasks like visual search.”

Source: Trends in cognitive sciences 11Shipp, S. (2004). The brain circuitry of attention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 223 – 230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.03.004

Each of the below terms refers to a specific aspect or type of attention (“mental bandwidth”), a complex cognitive process. 12Schweizer, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Goldhammer, F. (2005). The structure of the relationship between attention and intelligence. Intelligence, 33(6), 589 – 611. … Continue reading

Let’s explore different types of attention:

Each type of attention is likely to play a role in how we interact with and process information from our environment, and understanding these different aspects is key in fields like psychology, neuroscience, and education.

Learn more: The Anatomy of Attention

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

Annotations

| 1 | Silfwer, J. (2021, August 10). Online Wannabeism: Why We Mimic Social Media Influencers. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/online-wannabeism/ |

|---|---|

| 2 | Social mirror theory. (2023, July 21). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_mirror_theory |

| 3 | Lim, X. J., Radzol, A. M., Cheah, J.-H., & Wong, M. W. (2017). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 258 – 266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.022 |

| 4 | Ki, C. (2018, March). The Drivers and Impacts of Social Media Influencers: The Role of Mimicry. University of Tennessee. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/268799921.pdf |

| 5 | Silfwer, J. (2021, August 10). Online Wannabeism. Doctor Spin | the PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/online-wannabeism/ |

| 6 | Bernardini, J. (2014, June 30). The Infantilization of the Postmodern Adult and the Figure of Kidult. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291222595_The_Infantilization_of_the_Postmodern_Adult_and_the_Figure_of_Kidult |

| 7 | Silfwer, J. (2022, September 6). Social Media — The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/social-media/ |

| 8 | Silfwer, J. (2023, December 15). Echo Chambers: Algorithmic Confirmation Bias. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/echo-chambers/ |

| 9 | Silfwer, J. (2020, June 4). The Spiral of Silence. Doctor Spin | the PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/spiral-of-silence/ |

| 10 | Silfwer, J. (2023, November 22). The Anatomy of Attention. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/attention/ |

| 11 | Shipp, S. (2004). The brain circuitry of attention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 223 – 230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.03.004 |

| 12 | Schweizer, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Goldhammer, F. (2005). The structure of the relationship between attention and intelligence. Intelligence, 33(6), 589 – 611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2005.07.001 |