What are ‘publics’ in public relations?

Publics are fundamental to the public relations profession.

But what does this mean exactly?

And why does it matter?

Here we go:

The Publics in Public Relations

Publics are a central component of public relations — in fact, the ‘P’ in PR. However, they are often misunderstood or conflated with marketing’s ‘target groups’.

Here’s how to define publics in public relations:

Publics = psychographic segments (who) with similar communication behaviours (how) formed around specific issues (why) impacting a brand (to whom). 1Silfwer, J. (2015, June 11). The Publics in Public Relations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/publics-in-public-relations/

Please note:

Psychographic segment = similarities in cognitive driving factors such as reasoning, motivations, attitudes, etc.

Communication behaviours = how the public’s opinion is expressed (choice of message, rhetorical framing, and medium type).

Specific issue = determined situationally by a specific social object, often high on the agenda in news media or social media.

Learn more: The Publics in Public Relations

Publics vs Target Groups

In public relations (PR), publics is a central concept.

But in marketing contexts, you’ll hear mostly about target groups or target audiences.

What’s the difference?

Target Groups in Marketing

Marketing focuses on target groups mainly because of the historical tradition of buying third-party ad space. Ad space sellers preferred to describe their typical consumers by their demographic profile.

Some common demographic segments include:

For ads in traditional mass media, only demographic data was available.

Publics in Communications

With a primary focus on earned and owned media, it has always been about behaviours for the PR industry; therefore, we use publics (psychographic segmentation) instead.

Publics are situational groups that exhibit similar communicative behaviours, and their impact on an organisation is critical. These groups, formed by shared concerns or interests, can play a crucial role in shaping public opinion and determining the success or failure of an organisation’s PR efforts.

What’s the difference between demographic segmentation (typical for marketing) and psychographic segmentation (typical for public relations)?

Consider this example:

Imagine two ordinary individuals. Let’s call them Ben and Jerry. They both belong to the same demographic:

Demographically, Ben and Jerry seem more or less identical. So, are you likely to reach (and influence) both through the same media channels?

The short answer is — no.

Ben is hostile towards social media (“It’s a bloody waste of time!”) and prefers to read business newspapers over coffee in the morning. During the day, he listens to public radio on his commute to and from work. Ben mostly avoids the internet (“It’s only ads and trolls”).

But Jerry thinks (and acts) differently:

Jerry spends his nights in the basement, immersed in a Japanese World of Warcraft guild, collaborating with members worldwide; he’s a quintessential early adopter who streams television, listens to podcasts, and consumes news via social feeds.

In short: Ben and Jerry are demographically similar but psychographically different.

In public relations, we seek to understand how groups of individuals communicate. This is what matters for successful PR activities.

Learn more: Publics vs Target Groups (to be published)

Seriality: Context Matters

“Seriality” is a concept that emerges from identity and social theory, particularly in the works of philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Iris Marion Young. It refers to how individuals are grouped based on shared characteristics without a strong sense of belonging or identity.

Sartre argued that passive collectives, like people waiting at a bus stop, only become active when they recognise shared interests or struggle. Many publics remain “serial” (inactive) until activated by context. 2Sartre, J.-P. (1991). Critique of dialectical reason (Vol. 2, Q. Hoare, Trans.; A. Sheridan-Smith, Ed.). Verso. (Original work published 1985.) 3Silfwer, J. (2023, October 9). Five Types of Publics. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/five-types-of-publics/

“Seriality is a key concept in understanding the constancy and transformation of identity, particularly in public presentations of the self and its online manifestations.”

Source: M/C Journal 4Marshall, P. (2014). Seriality and Persona. M/C Journal, 17, 1 – 10. https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.802

In Sartre’s existentialist framework, seriality describes a form of social collectivity. According to him, people can be part of a series without necessarily sharing a unified group identity. For example, people waiting at a bus stop are connected by their shared situation (waiting for the bus) but do not necessarily form a cohesive public with a shared identity. They are separate individuals linked by a common objective or condition.

Key insights:

Seriality explains why some publics remain inactive and fragmented while others suddenly unite and how context (media, conflict, proximity, power structures) determines when, how, and why a group identity “clicks” into place.

Therefore, seriality is a way of understanding how individuals can belong to collective categories without necessarily having a shared demographic identity.

Learn more: Seriality (Context Matters)

Publics, Stakeholders, and Influencers

While marketing primarily focuses on target groups (demographic segmentation), public relations is focused on publics, stakeholders, and influencers (relational segmentation):

Publics = psychographic segments (who) with similar communication behaviours (how) formed around specific issues (why) impacting a brand (to whom). 7Silfwer, J. (2015, June 11). The Publics in Public Relations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/publics-in-public-relations/

Stakeholders = representatives of various vested interests directly or indirectly connected to a brand. 8Silfwer, J. (2021, January 5). The Stakeholders in Public Relations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/stakeholders-in-public-relations/

Influencers = independent content creators with influential platforms and followings of potential importance to a brand. 9Silfwer, J. (2020, January 15). The Influencers in Public Relations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/influencers-in-public-relations/

Learn more: Publics, Stakeholders, and Influencers (to be published)

John Dewey and the ‘P’ in Public Relations

The term “publics” can be traced back to the work of the American psychologist and philosopher John Dewey (1859 – 1952). 10John Dewey. (2023, March 25). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dewey

In his 1927 book, “The Public and Its Problems,” Dewey conceptualised publics as situational groups formed in response to shared concerns or issues. He posited that these groups emerge when individuals confront a common problem, recognise its existence, and take collective action to address it. 11Dewey, J. (1927). The Public and Its Problems. Athens, Ohio: Swallow Press.

“Dewey’s theory of the public sphere recognizes multiple publics and permeable borders between public and private, with communication playing a crucial role in public formation and re-formation.”

Source: Argumentation and Advocacy 12Asen, R. (2003). The Multiple Mr. Dewey: Multiple Publics and Permeable Borders in John Dewey’s Theory of the Public Sphere. Argumentation and Advocacy, 39, 174 — 188. … Continue reading

Dewey’s formulation of publics marked a significant departure from the traditional understanding of the “mass public,” which assumed a more homogeneous and passive audience.

By highlighting the situational and dynamic nature of publics, Dewey laid the foundation for a more nuanced and adaptive approach to understanding the complex interactions between organisations and their various audiences.

The term publics has become a cornerstone of modern public relations and communication theory.

This understanding of publics as situational and ever-changing highlighted the need for organisations to remain agile and adaptive in their communication efforts.

By recognising the diverse and situational nature of publics, PR professionals and communicators can better understand the needs and concerns of their various audiences, allowing them to develop more effective communication strategies.

“This recognition of the active and dynamic nature of publics has also influenced broader academic and public discourse, highlighting the importance of understanding and engaging with different groups of people who share common interests, concerns, or problems.”

Source: Contemporary Pragmatism 13Rogers, M. (2010). Introduction: Revisiting The Public and Its Problems. Contemporary Pragmatism, 7, 1 – 7. https://doi.org/10.1163/18758185 – 90000152

Learn more: John Dewey and the ‘P’ in Public Relations

Naming Publics in Public Relations

Publics are situational. They are formed when external factors create them. 14Blumer, H. (1946). The Mass, The Public and Public Opinion. In B. Berelson (Ed.), Reader in Public Opinion and Communication (pp. 45 – 50). 2nd ed. New York: Free Press. (Reprinted in 1966).

For instance, if a municipality announces the building of a new bridge, it might suddenly create several publics:

Where did I get those names from?

Well, the use of publics has no structural nomenclature. Identifying and naming publics creatively is part of the fun of using publics in public relations!

Publics: Example of a “PR Persona”

Fundamentals

Psychographics

Communication Style

Media Habits

Influences

Goals

Challenges

Learn more: How To Use Personas in PR

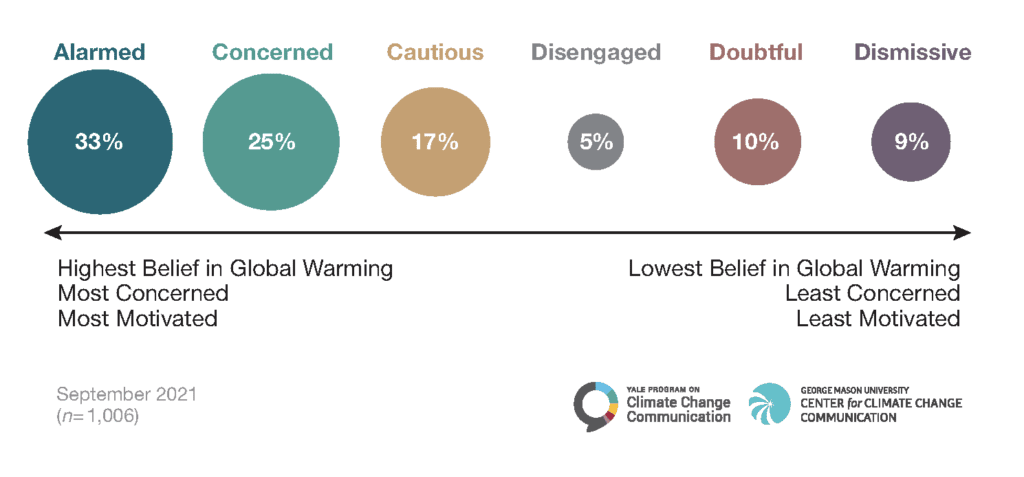

Case Study: Global Warming’s Six Americas

The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication has used questionnaires to survey US attitudes towards global warming. The program has identified six different publics:

Understanding different groups based on their perception of a specific issue provides valuable clues on how to best engage with the publics. 15Global Warming’s Six Americas — Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. (2023). Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. … Continue reading

The research makes it clear:

You need at least six communication strategies to successfully communicate about global warming in the US.

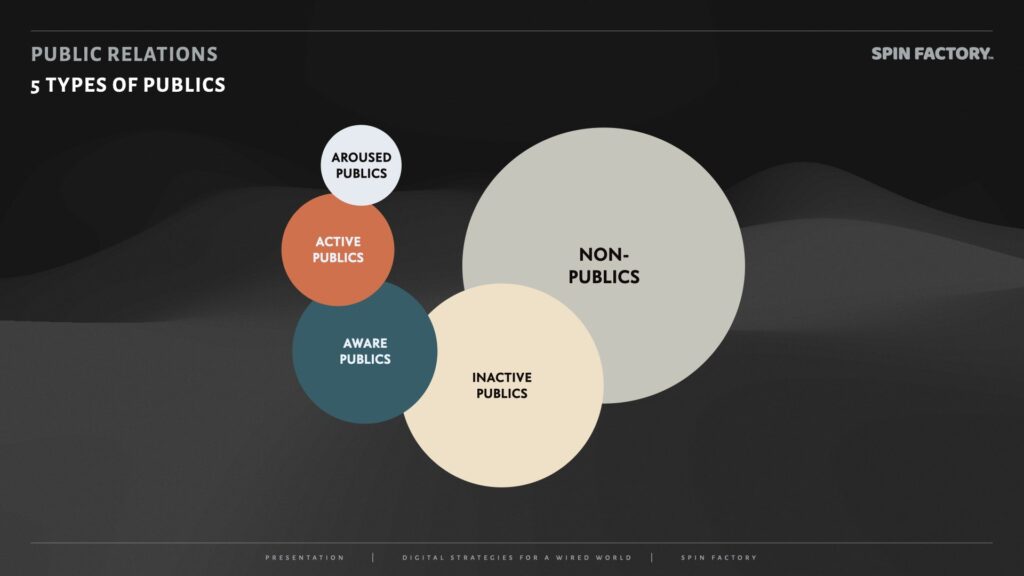

Five Types of Publics

There are plenty of inactive publics around us in society, just “waiting” for external situations to activate them and bring them together in coöperative, communicative behaviours.

However, PR tends to focus on the already activated publics:

“By focusing on activism and its consequences, recent public relations theory has largely ignored inactive publics, that is, stakeholder groups that demonstrate low levels of knowledge and involvement in the organisation or its products, services, candidates, or causes, but are important to an organisation.”

Source: Public Relations Review 16Hallahan, K. (2000). Inactive publics: The forgotten publics in public relations. Public Relations Review, 26(4), 499 – 515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(00)00061 – 8

Kirk Hallahan, Professor Emeritus, Journalism and Media Communication, Colorado State University, proposes five types of publics based on their knowledge and involvement: 17Hallahan, K. (2000). Inactive publics: The forgotten publics in public relations. Public Relations Review, 26(4), 499 – 515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(00)00061 – 8

Hallahan suggests a model based on knowledge and involvement:

As an organisation targeted by activists, what would be the best issue response? Hallahan proposes four principal response strategies: 18Hallahan, K. (2009, November 19). The Dynamics of Issues Activation and Response: An Issues Processes Model. Journal of Public Relations Research. … Continue reading

Learn more: Five Types of Publics

How To Identify (And Measure) Publics

Publics are often segmented by identifying and grouping existing communicative behaviours (outcomes). While it works for many situations, this approach a) focuses on activists, b) excludes inactive publics, and c) pushes the PR function to be reactive. 19Warner, M. (2002). Publics and Counterpublics. Public Culture, 14(1), 49 – 90.

A more fundamental approach is to focus on psychographic segments (psychological drivers) instead.

In practice, this can be done proactively using questionnaires and rating scales, interviews, reports (logs, journals, diaries etc.), and observations:

Using questionnaires for statistically relevant population subsets, PR professionals can proactively identify all types of publics.

Learn more: How To Measure Public Relations

Publics and Ethics

Traditional demographics (compared to psychographics) tell us little about how individuals consume their media and communicate.

When a brand is talking to me like I’m a white male in my early forties, a father and a husband, living in a Scandinavian capital, and working in the media industry (all of which is true, by the way) — I stop listening.

In the eyes of funnel fundamentalists, we are demographic entities stripped of our essence, mere puppets of consumption with wallets in place of hearts.

I’m not the sum of my socio-economic class, my job, age, location, ethnicity, sexuality, or my gender. Here at the precipice of the Electronic Age, we should all refrain from basing corporate activities on demographic stereotypes.

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

What should you study next?

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Spin’s PR School: Free Introduction PR Course

Get started with this free Introduction PR Course and learn essential public relations skills and concepts for future success in the PR industry.

Introducing Public Relations

Public Relations History

Publics in Public Relations

Comparing Public Relations

Public Relations Resources

Learn more: All Free PR Courses

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

Annotations

| 1, 7 | Silfwer, J. (2015, June 11). The Publics in Public Relations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/publics-in-public-relations/ |

|---|---|

| 2 | Sartre, J.-P. (1991). Critique of dialectical reason (Vol. 2, Q. Hoare, Trans.; A. Sheridan-Smith, Ed.). Verso. (Original work published 1985.) |

| 3, 6 | Silfwer, J. (2023, October 9). Five Types of Publics. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/five-types-of-publics/ |

| 4 | Marshall, P. (2014). Seriality and Persona. M/C Journal, 17, 1 – 10. https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.802 |

| 5 | Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Revised ed.). Verso. (Original work published 1983) |

| 8 | Silfwer, J. (2021, January 5). The Stakeholders in Public Relations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/stakeholders-in-public-relations/ |

| 9 | Silfwer, J. (2020, January 15). The Influencers in Public Relations. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/influencers-in-public-relations/ |

| 10 | John Dewey. (2023, March 25). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dewey |

| 11 | Dewey, J. (1927). The Public and Its Problems. Athens, Ohio: Swallow Press. |

| 12 | Asen, R. (2003). The Multiple Mr. Dewey: Multiple Publics and Permeable Borders in John Dewey’s Theory of the Public Sphere. Argumentation and Advocacy, 39, 174 — 188. https://doi.org/10.1080/00028533.2003.11821585 |

| 13 | Rogers, M. (2010). Introduction: Revisiting The Public and Its Problems. Contemporary Pragmatism, 7, 1 – 7. https://doi.org/10.1163/18758185 – 90000152 |

| 14 | Blumer, H. (1946). The Mass, The Public and Public Opinion. In B. Berelson (Ed.), Reader in Public Opinion and Communication (pp. 45 – 50). 2nd ed. New York: Free Press. (Reprinted in 1966). |

| 15 | Global Warming’s Six Americas — Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. (2023). Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/ |

| 16, 17 | Hallahan, K. (2000). Inactive publics: The forgotten publics in public relations. Public Relations Review, 26(4), 499 – 515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(00)00061 – 8 |

| 18 | Hallahan, K. (2009, November 19). The Dynamics of Issues Activation and Response: An Issues Processes Model. Journal of Public Relations Research. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S1532754XJPRR1301_3 |

| 19 | Warner, M. (2002). Publics and Counterpublics. Public Culture, 14(1), 49 – 90. |