The power of slow storytelling is making a comeback.

Must everything be shorter and faster on the internet?

It seems as if slow storytelling is making a comeback. Longer television shows, longer games, longer YouTube videos, longer tweets, longer blog articles — longer everything.

Why?

Here we go:

The Paradigm of Fast Storytelling

The narrative speed has accelerated. News cycles are flashing by. Updates and tweets are blazing by. Social media is turning into show business.

Twenty-four-seven news cycles and bite-sized advertising masquerading as entertainment are coming at us like a furious swarm of moths clouding the sky.

Yes, some are concerned. Social media pessimists are foreboding the decline of civilisation due to our shorter attention spans and notification addictions.

Everything must be short:

We’re all in a collective hurry and can’t be bothered with too much context. “It’s just the way it is now,” I think.

Click, click.

The Counter-Reaction

I grew up on the island of Alnö with about 900 fellow dwellers. I moved away, got my strategic communication and linguistic degrees, and ended up in Stockholm, the capital of Sweden.

In Stockholm, I remember being astounded by the impatience of the city slickers; they sighed as they missed their subway ride — even though the next one was in just a few minutes.

On Alnö, buses came by once every hour on weekdays.

A city-life decade later, having lived in Stockholm, London, and New York, I find myself being immersed in this Pavlovian conditioning.

A five-second break today? No problem. That’s enough to check my social feeds, calendar, and inbox, read a few headlines and check directions on Google Maps.

In short: We’ve all picked up the pace.

Now, we’re long overdue for a counter-reaction.

Mental Bandwidth and Narratives

Suppose Dunbar’s number dictates the optimal number of personal relationships in a group. Why can’t we assume that there’s also a cognitive limit to the number of narratives we can stay invested in? 1Silfwer, J. (2023, June 7). 150 — Dunbar’s Number. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/150-dunbars-number/

There’s comprehensive scientific support for the idea that we filter all incoming inputs. We discard these inputs or assign them to a few more prominent storylines that we’re already invested in. 2Silfwer, J. (2023, November 30). Cognitive Dissonance: Mental Harmony Above All Else. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/cognitive-dissonance/.

The digital content explosion of available information might negatively affect everything from attention spans to cognitive overloading. Still, the Industrial Revolution also brought its fair share of less-than-fortunate outcomes. 3Silfwer, J. (2023, March 20). The AI Content Explosion. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/ai-content-explosion/

Remember, our mental bandwidth has remained unchanged for at least 200,000 years. 4If anything, our brains are shrinking. Over the past 20,000 years, the average volume of the human male brain has decreased from 1,500 cubic centimetres to 1,350 ccs, losing a chunk the size of a … Continue reading

Television Series and Superhero Universes

Lately, the charm of watching a full-length movie has been rapidly declining; the story arc in a typical two-hour blockbuster is too short for me; there’s not enough time to get to know and understand the characters of the movie, and the suspension of disbelief suffers from being forcefully paced.

This is, in my case, thanks to Netflix. 5Silfwer, J. (2013, February 2). House Of Cards is Changing the Streaming Game. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/house-of-cards/

I don’t watch Netflix for its variety of movies; I binge on their television shows (albeit that “television” sounds old-fashioned). An episode is arguably much shorter than a full-length movie, but the storytelling spans seasons instead of minutes.

ScreenRant lists 15 reasons why television shows are superior to movies:

I’ve spent many hours following in the footsteps of “The Walking Dead” and its main protagonist, Rick Grimes. As a viewer, I’ve been invested in Rick’s life’s ups and downs (mostly downs) for a long time, but I still have no idea whether he will make it.

There’s no denying the literary quality of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic saga, The Lord of the Rings. Still, when it comes to silver screen adaptations, it’s tough for LOTR director Peter Jackson to compete with the richness of lore in shows like Game of Thrones, where the storytelling spans season after season.

And it seems like moviemakers are catching on, too.

See how Marvel’s stringing typical blockbuster-length movies together to create longer arcs for their characters and add more depth to their cinematic Marvel universe.

Games as Long-Form Storytelling

Watching Let’s Play walkthroughs on YouTube is my guilty pleasure (or obsession?).

I’ve been at the edge of my seat through games like “The Last of Us,” “Detroit Become Human,” and “Uncharted.” I’ve discovered new worlds through games like “God of War,” “Far Cry,” and “Assassin’s Creed.”

In-game storytelling has seen tremendous development over the last couple of years. Watching social media naturals play their way through a good narrative is immersive and captivating, even if you don’t play these games yourself. 6Silfwer, J. (2010, April). Social Media Naturals. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/social-media-naturals/

More giant story-driven games might take a skilled player up to 40 hours of active gameplay to get through, especially if they are into exploring and side missions.

For instance, the anticipated title Red Dead Redemption 2 delivers an impressive 60+ hour story campaign:

Read also: DayZ for Days

Long-Form Content in Search Engines

Longer forms have other advantages, too.

If you’re into digital marketing or communications, you’ve probably thought about how to rank on the first pages of Google’s SERP (search engine results page) for your keywords.

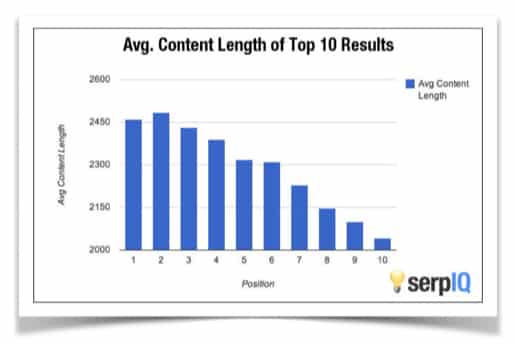

A study by SerpIQ suggests that 2,450 words are the “sweet spot” for ranking 1 – 10 on Google: 7A study by Moz indicates that long-form blog posts tend to do better in search rankings and social media.

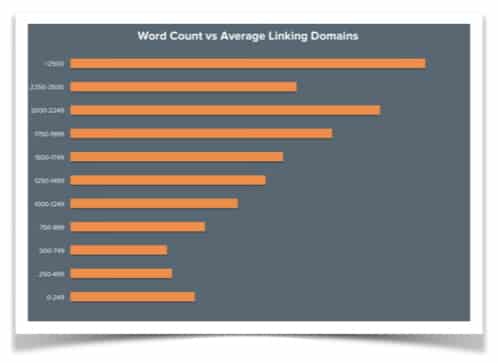

Also, according to Hubspot, you get more backlinks as well:

(And for those who don’t write articles that often, 2,000 words are quite a decent length: you’ve barely read 900 words of this article!)

I’m not suggesting that longer is always better in every way. However, we might have underestimated our basic human need for depth and context — especially in this fast-paced, digital-first landscape.

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

PR Resource: Free Storytelling PR Course

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Spin’s PR School: Free Storytelling PR Course

Elevate your public relations game with this free Storytelling PR Course. Learn essential and timeless storytelling techniques for effective communication.

Storytelling Elements

Storytelling Scripts

Storytelling Inspiration

Learn more: All Free PR Courses

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

Annotations

| 1 | Silfwer, J. (2023, June 7). 150 — Dunbar’s Number. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/150-dunbars-number/ |

|---|---|

| 2 | Silfwer, J. (2023, November 30). Cognitive Dissonance: Mental Harmony Above All Else. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/cognitive-dissonance/ |

| 3 | Silfwer, J. (2023, March 20). The AI Content Explosion. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/ai-content-explosion/ |

| 4 | If anything, our brains are shrinking. Over the past 20,000 years, the average volume of the human male brain has decreased from 1,500 cubic centimetres to 1,350 ccs, losing a chunk the size of a tennis ball. |

| 5 | Silfwer, J. (2013, February 2). House Of Cards is Changing the Streaming Game. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/house-of-cards/ |

| 6 | Silfwer, J. (2010, April). Social Media Naturals. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/social-media-naturals/ |

| 7 | A study by Moz indicates that long-form blog posts tend to do better in search rankings and social media. |