There are growing concerns about how social media divides us.

As it becomes easier for everyone to self-publish without censorship, we also see the rise of anonymous hate, fraudulent behaviour, online trolls, rampant populism, and propaganda.

And then there’s the techlash.

Oh, and haven’t you heard? Social media is killing journalism and culture, too.

Can the general public be trusted to wield such powers if the internet is truly mightier than the sword?

Here we go:

Social Media Divides Us Academically

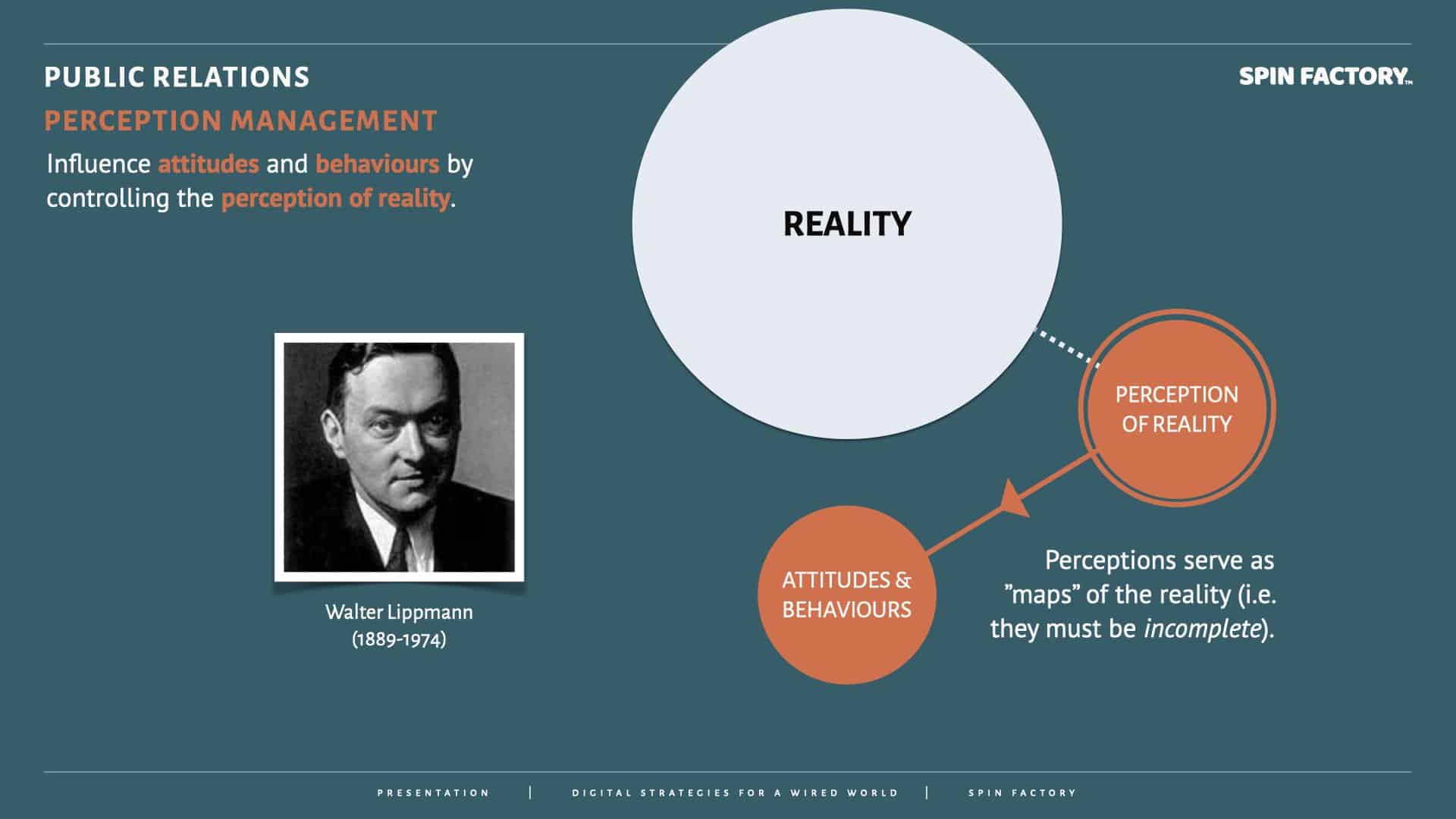

Walter Lippmann (1889 – 1974) was an American writer, political commentator, and columnist. His legacy still lingers, as he coined concepts like “the Cold War” and words like “stereotype.” His most notable publication, Public Opinion (1922), is still noteworthy for public relations professionals.

Walter Lippmann and Perception Management

In his seminal work Public Opinion (1922), Walter Lippmann laid the intellectual groundwork for the idea that perception and reality are not the same — a core principle of modern perception management. 1Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan.

Lippmann argued that:

Lippmann’s ideas resonate deeply with perception management in public relations.

“We are all captives of the picture in our head — our belief that the world we have experienced is the world that really exists.”

— Walter Lippmann (1889 – 1974)

On Creating Pseudo-Environments

Lippmann coined the term “pseudo-environment,” which describes the filtered, biased, and often artificial version of reality presented by the media. He warned that influential elites could exploit this manufactured reality to manipulate public thought and behaviour.

Lippmann was sceptical about the public’s ability to discern reality from the pseudo-environment, which raises ethical concerns:

Perception management is not inherently sinister, but as Lippmann warned, it places immense power in the hands of those controlling the narrative.

In essence, perception management is the applied PR version of Lippmann’s media critique. It acknowledges that facts alone do not win public trust—priming, framing, storytelling, and emotional appeal do.

Learn more: Perception Management

Lippmann, the winner of two Pulitzer prizes, engaged in heated public debates with John Dewey (1859−1952), an American philosopher and psychologist of specific interest in public relations. His perspective of human interaction gave rise to segmenting people in publics (the “P” in public relations). 2The Lippmann-Dewey debate was an intellectual battle concerning the role of journalism. Can the general public comprehend the value of serious reporting, or will they opt for entertainment instead?

Dewey critiqued Lippmann’s “elitist views”, while Lippmann emphasised the importance of journalism; the public cannot make sense of the world without objective reporting and expert insights.

Edward Bernays (1891−1995) argued that mass media was a propaganda tool for the elites, the father of public relations.

Another influential PR practitioner, Ivy Lee (187−1934), who, amongst other accomplishments, created the first press release and influenced the field of crisis communications, seemed to have much more faith in humanity’s capacity for understanding the world.

On Lippmann’s side of things, we see critical minds like Noam Chomsky discussing the manufacturing of consent, and on Dewey’s side, we find minds like Clay Shirky discussing, here comes everybody. While Chomsky would argue that our media is primarily a tool for the élite to shape our minds, Shirky would likely say that we as individuals have absolute power (“there’s no information overload, only filter failure”).

Neil Postman (1931−2003) warned us about amusing ourselves to death, while Marshall McLuhan (1911−1980) demoted the importance of specific content by stating that the medium is the message.

From a foundational standpoint, there are reasonable arguments from both sides of the spectrum.

Social Media Divides Us Individually

Today, those who believe in the power of social media will argue that everyone’s a publisher with a powerful voice and that social graphs are redefining how we relate to each other. They are social media optimists about how the media landscape is changing, and they typically believe that we’re simply in the process of learning how to manage the digital media landscape.

Social media optimists will argue that if there’s a problem with how humans behave, we should embrace the fact that technology brings these behaviours out in the open. Only then can we learn, as a society, how to deal with such serious issues.

Then, we have social media pessimists who will argue that social media is a breeding ground for fake news, populism, and the subsequent death of one of the essential pillars of democracy — journalism. They’re also the driving force behind the techlash, seriously critiquing the tech giants.

“The wisdom of crowds” is beautiful, but is it also naïve? Wikipedia is a remarkable achievement and couldn’t exist without its community of volunteers. WordPress powers 26% of the web and runs on open-source contributions from programmers worldwide.

Still, pessimists don’t feel that whatever good social media is doing is enough to make up for making us addicted to smartphones and promoting further polarization.

Social Media Divides Us Algorithmically

In the wake of the recent US election, where President Donald Trump won the populist voters, the founder of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, has been heavily criticised for aiding and abetting the dissemination of peak populism.

Facebook and most other social media platforms are being heavily criticised for creating filter bubbles where like-minded people amplify their delusions by social reinforcement — instead of listening to well-educated experts on relevant subject matters.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal didn’t precisely strengthen Facebook’s case.

Governments and institutions are going after the tech giants worldwide, but are their goals altruistic? Or are our governments trying to get their hands on our data themselves?

With profound advancements in narrow artificial intelligence, social scoring systems and facial recognition, there’s a case to be made that it’s better to see innovation driven by companies that run ads rather than institutions that monopolise violence.

Still, putting the macro power balance aside, there’s the pressing underlying issue of social media algorithms promoting media logic mechanisms, i.e. polarisation, simplification, personalisation, and visualisation.

Either way, there’s an apparent risk that powerful agents like states and tech giants are taking advantage of adverse side effects to push for more power and incredible wealth — at the expense of us social media users.

Social Media Divides Us Politically

The conflict between news publishers and tech giants fighting for a share of voice and ad revenue isn’t made better. This conflict often forces news publishers to side with the state’s agenda, not the people’s.

Still, our social media usage is deeply ingrained in our communicative behaviour. Companies like Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google (FAANG) are already influencing our media consumption at an unprecedented level.

Consequently, journalists and traditional news publishers, the former champions of free speech and freedom from censorship, are pushing tech giants like Facebook to take responsibility for how we, the social media users, leverage the freedom of speech.

Still, we must ask ourselves if we want the FAANG companies to actively use their algorithms to shape our worldview.

A significant issue is that today’s political landscape is driven by its flanks. On the one side, we have alt-right nationalists and populists, and on the other, we have alt-left social justice warriors. While far apart politically, they’re both heavily reliant on identity politics, centralised power, and intolerance of differing opinions.

Both flanks see aggression and violence as reasonable political methods, highly favoured expressions amplified by social media algorithms.

So, no matter if Mark Zuckerberg were to take the stance of being a social media optimist or a social media pessimist, he wouldn’t know which leg to stand on:

If the tech giants leave the social algorithms unchecked, they fuel the flanks.

They fuel the flanks if they manipulate the algorithms to stabilise human behaviour.

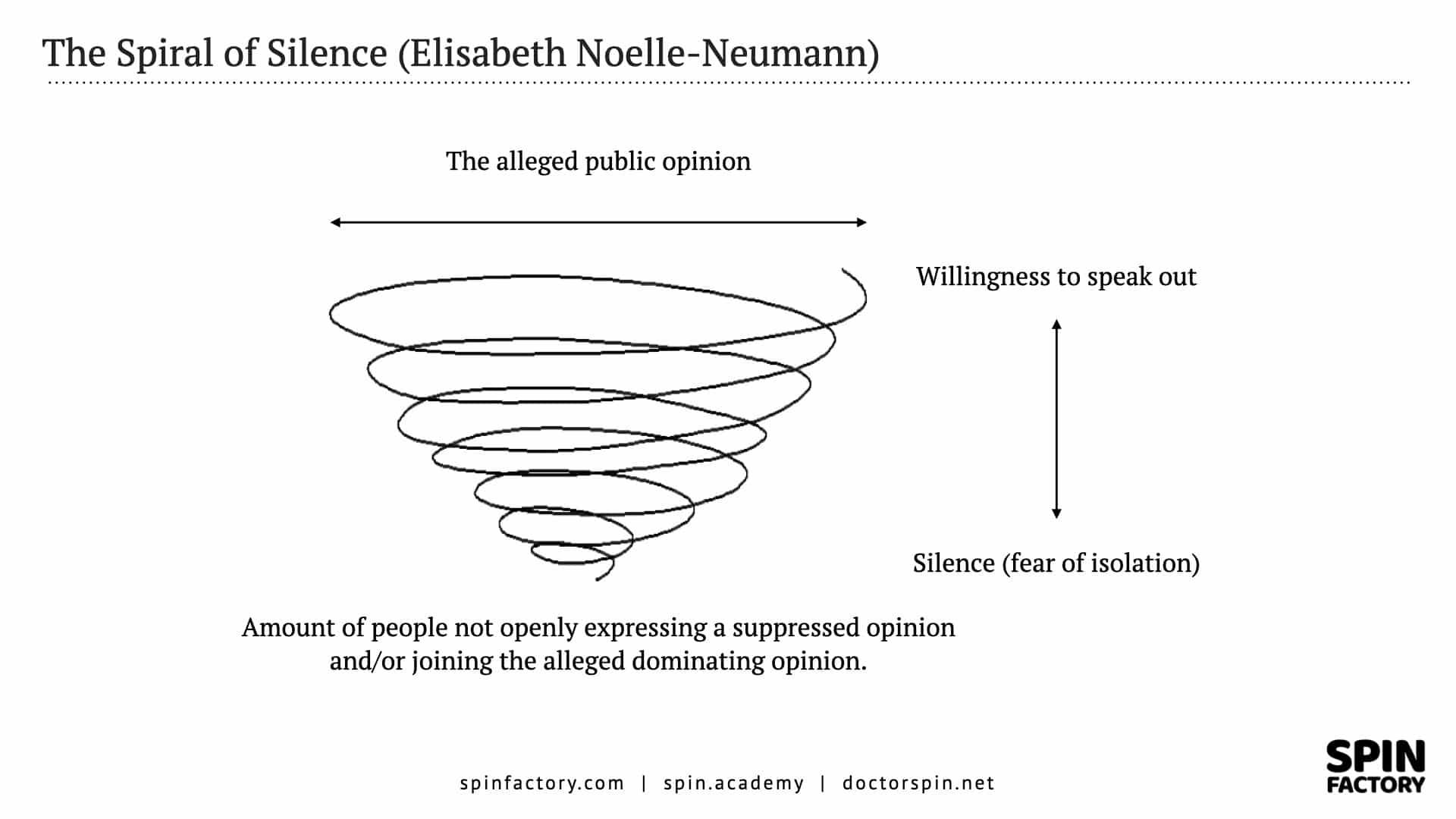

And doing nothing accelerates the spiral of silence.

How To Stop Social Media From Dividing Us

As the recent debate on how social media is responsible for spreading fake news and alternative facts stirs emotions, many raise their voices for stricter regulation and increased control. We mustn’t socialise ourselves to death, it seems.

Neil Postman warned us about the dangers of media logic and the risk of “amusing ourselves to death”.

While television indeed changed the fabric of our society for both better and worse, we must ask ourselves if we believe that state-controlled television used to control our worldviews and emotional states would have been preferable. Or if it’s even possible to stop information technology from changing our lives?

As social media users, we must be careful about our wishes.

The question of how social media divides us is complex, so what kind of change should we demand from those in power?

We should lobby for…

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

PR Resource: Social Media Logic

Enter: Social Media Logic

Media logic is a set of theories describing how the medium affects the media. Typically, the format (as the medium dictates) influences the mediated message.

“Media logic is defined as a form of communication, and the process through which media transmit and communicate information. The logic and guidelines become taken for granted, often institutionalized, and inform social interaction. A basic principle is that media, information technologies, and communication formats can affect events and social activities.“

Source: The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication 3Altheide, D. L. (2016). Media Logic. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication, 1 – 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc088

As famously stipulated by Marshall McLuhan, “The medium is the message.” What are the typical effects of media logic on mediated messages?

Classic Media Logic Effects

Classic media logic is hypothesised to influence the news media in the following ways: 4Nord, L., & Strömbäck, J. (2002, January). Tio dagar som skakade världen. En studie av mediernas beskrivningar av terrorattackerna mot USA och kriget i Afghanistan hösten 2001. … Continue reading

The effects of the above media logic can also be recognised in social media. Still, social network algorithms seem to add even more effects:

Social Media Logic Effects

“Social media logic, rooted in programmability, popularity, connectivity, and datafication, is increasingly entangled with mass media logic, impacting various areas of public life.”

Source: Writing Technologies eJournal 5Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding Social Media Logic. Writing Technologies eJournal. https://doi.org/10.17645/MAC.V1I1.70

Based on the suggested additions for social platforms, we can add four extra dimensions to the classic media logic effects model:

Social media logic seems entangled with classic media logic. While more complex, social networks seem to amplify the effects of classic media logic.

Learn more: Social Media Logic

PR Resource: The Amplification Hypothesis

The Amplification Hypothesis

It’s common to find that counterarguments strengthen existing beliefs instead of weakening them.

The harder you attack someone verbally, the more you convince them of their belief, not yours.

The phenomenon is known as the amplification hypothesis, where displaying certainty about an attitude when talking with another person increases and hardens that attitude.

“Across experiments, it is demonstrated that increasing attitude certainty strengthens attitudes (e.g., increases their resistance to persuasion) when attitudes are univalent but weakens attitudes (e.g., decreases their resistance to persuasion) when attitudes are ambivalent. These results are consistent with the amplification hypothesis.“

Source: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 6Clarkson, J. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Rucker, D. D. (2008). A new look at the consequences of attitude certainty: The amplification hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, … Continue reading

How does the amplification hypothesis work?

In a threatening situation or emergency, we resort to the primal (fastest) part of the brain and survival instincts (fight, flight and freeze). 7Surviving the Storm: Understanding the Nature of Attacks held at Animal Care Expo, 2011 in Orlando, FL.

Establishing common ground and exhibiting empathy demonstrates a genuine understanding of their perspective, fostering trust and openness to your ideas. Conversely, a strategic mismatch of attitudes can serve as a powerful countermeasure if your objective is to deflect persuasive attempts.

Persuade

To persuade, align your attitude with the target. Otherwise, you will only act to create resistance.

Provoke

To put off a persuader, mismatch their attitudes. When they are logical, be emotional, and vice versa.

Learn more: The Amplification Hypothesis: How To Counter Extreme Positions

PR Resource: Spiral of Silence

The Spiral of Silence Theory

Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann’s (1916 – 2010) well-documented theory on the spiral of silence (1974) explains why the fear of isolation due to peer exclusion will pressure publics to silence their opinions.

The theory was developed in the late 1970s in West Germany, partly in response to Noelle-Neumann’s observations of how public opinion seemed to shift during the Nazi régime and post-war Germany.

The spiral of silence theory is based on the idea that people fear social isolation. This fear influences their willingness to express their opinions, especially if they believe these opinions are in the minority.

Rather than risking social isolation, many choose silence over expressing their opinions.

As the dominant coalition stands unopposed, they push the confines of what’s acceptable down a narrower and narrower funnel, the so-called opinion corridor). 11Opinion corridor. (2023, April 8). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opinion_corridor

Noelle-Neumann emphasised the media’s role in shaping public perception of what opinions are dominant or popular, thus influencing the spiral of silence.

Populism and Cancel Culture

The mechanisms behind Elisabeth Noelle Neumann’s spiral of silence theory could fuel destructive societal phenomena like populism and cancel culture:

In both cases, the spiral of silence contributes to a polarised environment. Views become dominant not necessarily because they are more popular but because opposing views are not expressed due to fear of social isolation or repercussions.

Learn more: The Spiral of Silence

Annotations

| 1 | Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan. |

|---|---|

| 2 | The Lippmann-Dewey debate was an intellectual battle concerning the role of journalism. Can the general public comprehend the value of serious reporting, or will they opt for entertainment instead? |

| 3 | Altheide, D. L. (2016). Media Logic. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication, 1 – 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc088 |

| 4 | Nord, L., & Strömbäck, J. (2002, January). Tio dagar som skakade världen. En studie av mediernas beskrivningar av terrorattackerna mot USA och kriget i Afghanistan hösten 2001. ResearchGate; Styrelsen för psykologiskt försvar. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271014624_Tio_dagar_som_skakade_varlden_En_studie_av_mediernas_beskrivningar_av_terrorattackerna_mot_USA_och_kriget_i_Afghanistan_hosten_2001 |

| 5 | Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding Social Media Logic. Writing Technologies eJournal. https://doi.org/10.17645/MAC.V1I1.70 |

| 6 | Clarkson, J. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Rucker, D. D. (2008). A new look at the consequences of attitude certainty: The amplification hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(4), 810 – 825. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013192 |

| 7 | Surviving the Storm: Understanding the Nature of Attacks held at Animal Care Expo, 2011 in Orlando, FL. |

| 8 | Silfwer, J. (2017, June 13). Conversion Theory — Disproportionate Minority Influence. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/conversion-theory/ |

| 9 | Beck (1999): Homogenization, Dehumanization and Demonization. |

| 10 | Cognitive dissonance. (2023, November 20). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_dissonance |

| 11 | Opinion corridor. (2023, April 8). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opinion_corridor |

| 12 | Silfwer, J. (2018, August 6). How To Fight Populism. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/how-to-fight-populism/ |

| 13 | Silfwer, J. (2020, August 24). Cancel Culture is Evil. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/cancel-culture/ |