The acceleration theory can help you crush your competition.

At times in life, it might seem like everyone is ahead.

At such times, you might experience stress, self-doubt, and performance anxiety — especially if you have a competitive personality.

Struggling to stay ahead at all times might be draining mentally and physically. Just keeping up becomes a chore.

Turns out that staying ahead might also be overrated. I came to this conclusion when researching how to become a better sprinter.

Here we go:

My Sprint Experiment in Greenwich Park

In 2004, I lived in Greenwich, London. My girlfriend and I rented a rundown apartment near Cutty Sark above a local post office.

Broke and restless, we spent much time exercising in Greenwich Park, home of the GMT date line. The park was an excellent place to play around with a stopwatch and some sprints.

Why not? We were both strong sprinters in high school and wanted to see if we could still hit some decent times.

I quickly learned I wasn’t even close to my high school records. As disappointing as this was, I added some interval training to my regimen. I pushed myself hard but could not slow down my new, slow times.

Whatever speed I had as a teenager now seemed to be gone.

Still, I wasn’t ready to give up.

I turned to research.

Inspired by World Champions

I remember watching the 100-meter dash in the Olympics as a kid. I was mesmerised by how some sprinters could come up from behind in the last part of the race and crush their opponents.

But at the same time, I always wondered:

If an élite sprinter is leading the 100-meter dash at 80 meters and someone else is coming up fast from behind, why isn’t the pack leader putting up more of a fight?

I reasoned that something must be left in the tank with only 20 meters to the finish line. But no. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a 100-meter dash sprinter pick up the pace that close to the finish line.

Naturally, I started searching for how the 100-meter dash works from a mathematical perspective.

I will use some interesting data points from Maurice Green and Usain Bolt to illustrate some of my findings:

Data Points from Maurice Green

In his paper, A Mathematical Model of the 100M and What It Means, Kevin Prendergast outlines a formula for describing what happens during a 100-meter dash. Prendergast tests his proof on the results from the 1999 World Championships, where data from the eight finalists were analysed. Seven sprinters were then grouped and compared to the winner, Maurice Greene. 1Prendergast, K. (2018, January 21). A mathematical model of the 100m and what it means. Silo. https://silo.tips/download/a‑mathematical-model-of-the-100m-and-what-it-means

Data points from the sprinters (excluding Maurice Greene) in that race showed:

And here are the same data points, but for Maurice Greene alone:

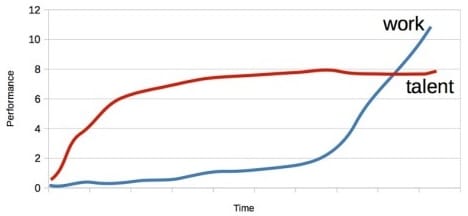

The seven finalists reached their points of maximum speed at an average of 59.79 meters into the race, at which point Maurice Green was still accelerating, reaching his maximum speed at 86.84 meters! It shows in the duration of acceleration, which for Greene was 8,68 seconds (almost the entire race!) and 6,44 seconds for the rest.

Greene’s max speed wasn’t much higher than the others, but the others decelerated for 3.38 seconds while Greene only slowed down for 0.99 seconds.

Prendergast concludes:

“The practical lesson from this model for sprinters and coaches would seem to be the benefit of extending the time of acceleration. This, rather than raw power out of the blocks, will result in faster times. It is probably a matter of control. […] It is possible to derive a mathematical model that models a 100m performance very well. It provides valuable information on the makeup of the performance, regarding acceleration, velocity, and distance at any stage in the race. It enables us to see the vital ingredients of success in 100m running, and that the most vital is to accelerate as long as possible.”

Data Points from Usain Bolt

Assuming that the friction between our feet and the ground is constant and that running on two feet is given, a theoretical superhuman can run 100 meters between 4,5 to 5 seconds.

Going any faster is impossible without altering physics.

But here’s the exciting part:

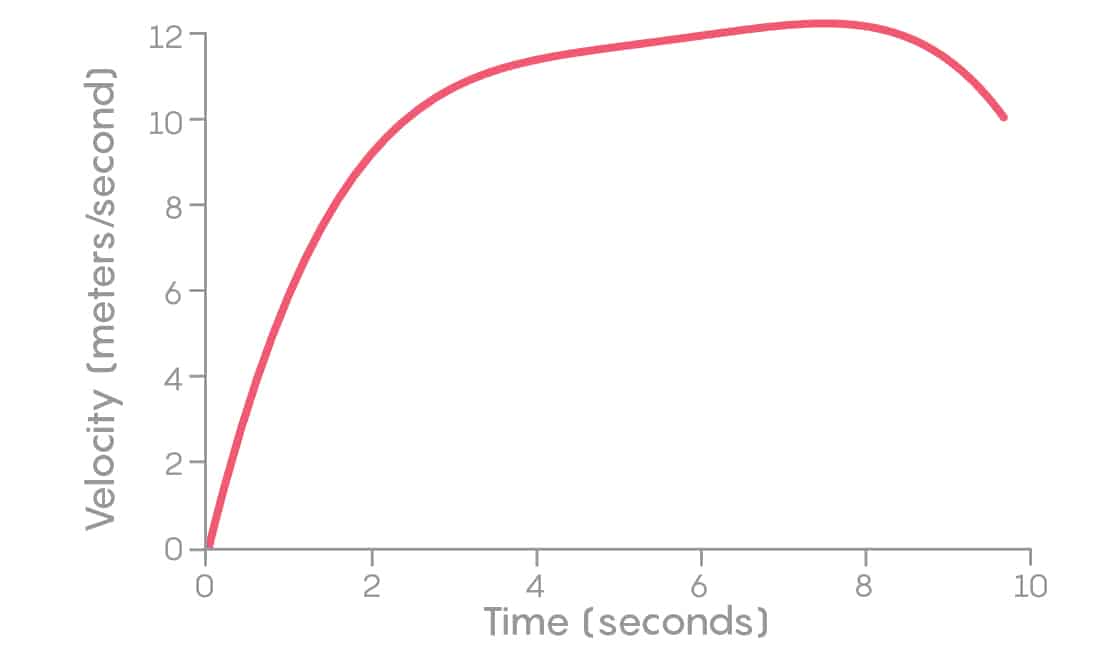

Look at the velocity curve for the world’s fastest sprinter, Usain Bolt.

When I looked at breakdowns for famous 100-meter sprinters over the last 40 years, their average top speeds hadn’t increased much, but Usain Bolt stands out with his maximum speed of 12,2 meters per second.

We can see that Bolt’s speed varies during a 100-meter dash. So, what can we discern from his data points? I looked closely at several 100-meter dash finals.

The acceleration phase: To accelerate, you must be at an angle with the ground (leaning forward, pushing with legs) to be able to push hard against gravity.

The top speed phase: Once upright (running tall with as little contact with the ground as possible), you can only maintain speed or decelerate.

Turns out I’ve been wrong about sprinting. I always tried to reach my top speed as fast as possible in my sprints.

The world’s best 100-meter dash sprinters can only maintain their top speeds for 20 – 25 meters. Maurice Green accelerated for an incredible 8,69 seconds and kept his top speed for 0,99 seconds.

And what was I doing? I cruised easily at my “top speed” for 75 – 80 meters.

Huh.

How fast would I have to run at a top speed that I could only sustain for no more than 20 – 25 meters? I realised that I should try to extend my acceleration phase.

Time for a new experiment.

Back to Greenwich Park: New Experiment!

My girlfriend and I went back to Greenwich Park, marked every 10 meters along a 100-meter track, and I made a few test sprints.

First, I ran as usual. I reached my top speed (running tall with as little contact with the ground as possible) after about 25 – 30 meters, and I managed to keep my speed reasonably well for the remainder of the distance.

Now, I wanted to extend my acceleration time. But for how long? I decided to go for the 60-meter mark.

I prepared myself, and as my girlfriend started the stopwatch, I got off to a good start. As I kept accelerating, the strain on my body was immense. At the 30-meter mark, I felt like I was carrying an elephant. At the 40-meter mark, I could not keep accelerating for longer.

And as I began closing in on the finish line, my legs and upper body were spent. At 80 – 90 meters, I could feel myself decelerating.

Reaching the finishing line felt like an eternity. Also, I felt a lot more drag throughout the sprint, almost as if someone had attached a parachute to my waist, slowing me down even further.

Discouraged, I asked my girlfriend about my time.

“Well, Jerry, that was your fastest 100-meter dash ever,” she said while staring at the stopwatch like she couldn’t believe it. “By a wide margin.”

The Acceleration Theory

“Do today what others won’t, so tomorrow you can do what others can’t.”

According to Prendergast’s mathematical model for élite sprinters, getting an early lead can harm your finishing time. 2Prendergast, K. (2018, January 21). A mathematical model of the 100m and what it means. Silo. https://silo.tips/download/a‑mathematical-model-of-the-100m-and-what-it-means

Can you apply an “acceleration theory” outside sprinting?

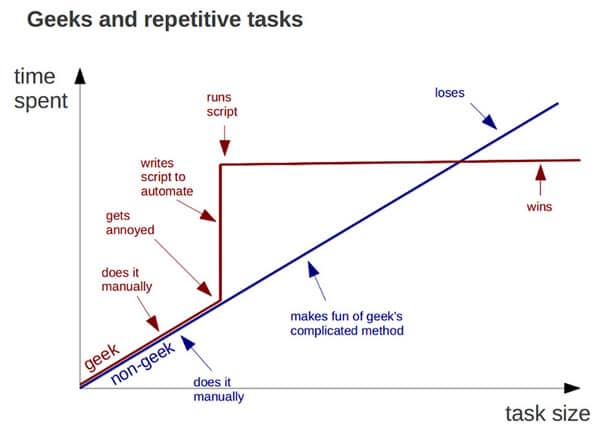

Well, it seems to me that you can sometimes ensure a win by staying in a zone that many find uncomfortable for longer.

My acceleration phase philosophy is as follows: At the beginning of a new and challenging endeavour, you work hard on improving, not minding that others reap more of the initial benefits.

Acceleration theory (mental model). This concept indicates that the winner mustn’t lead the race from start to finish. Mathematically, delaying maximum “speed” by prolonging the slower acceleration phase will get you across the finish line faster. 3Silfwer, J. (2012, October 31). The Acceleration Theory: Use Momentum To Finish First. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/acceleration-theory/

Instead, you ignore your competition at first, striving to keep accelerating well past the halfway point of the endeavour. At the 60% mark, you put everything you learnt and built up into play — and you go!

The Intriguing 60% Mark

Based on the mathematical model for sprinters, I often contemplate the switch from the acceleration to the top speed phase. According to the equation, the switch should happen at around 60% of the race.4Prendergast, K. (2018, January 21). A mathematical model of the 100m and what it means. Silo. https://silo.tips/download/a‑mathematical-model-of-the-100m-and-what-it-means

If we play around with this idea:

It’s anecdotal and not a “theory,” sure.

However, the approach of prolonging the acceleration phase has served me well.

Example: When working with a PR client, I typically spend 60% of the initial project scope doing necessary groundwork, asking uncomfortable questions, doing deep research, preparing, running tests, compiling materials, etc.

Key Takeaways: What To Know

Please remember: Your competitors are not necessarily “ahead.” Lots of people are impatient and peak too soon.

Here are the key takeaways from this mindset:

Know what done (100%) looks like. Always know the distance for a particular undertaking (i.e. the equivalent of knowing where the finish line will be).

Know what acceleration (<60%) looks like. Hunker down and accelerate continuously. Never mind about your competition; focus on the hard work of gaining momentum.

Know what top speed (>60%) looks like. Get up straight and maintain your hard-earned top speed. Be mindful of maintaining good form, and don’t try to get back into accelerating again.

Learn more: The Acceleration Theory

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

PR Resource: Life Design

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Personal Projects: Life Design Ideas

In addition to being a PR professional, I strive to live smarter, and I sometimes stumble upon ideas worth writing down when I consider these matters.

Life Design Ideas

Learn more: Lifestyle Design

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

Annotations

| 1, 2, 4 | Prendergast, K. (2018, January 21). A mathematical model of the 100m and what it means. Silo. https://silo.tips/download/a‑mathematical-model-of-the-100m-and-what-it-means |

|---|---|

| 3 | Silfwer, J. (2012, October 31). The Acceleration Theory: Use Momentum To Finish First. Doctor Spin | The PR Blog. https://doctorspin.net/acceleration-theory/ |