I met an old founder who allowed the media to destroy him.

Many years ago, I got an email about a company in a severe crisis. The email was sent from a worried and concerned family member to the founder and acting CEO.

I knew about the company since the crisis had been plastered all over the news for a few days. I remember reading the newspapers, thinking that “this company is neck-deep in crap.”

So, I called the old founder up. He was an older man who started young and built the company from the ground up. He seemed very confident and not startled by the commotion around his company; however, he felt he could use professional help to manage the media storm.

A PR colleague and I jumped on a plane.

I was feeling a bit uneasy about the whole thing. I help organisations communicate better for a living, and that’s a good reason to get up in the morning …

… but would this be a case of helping evil forces evade what’s rightfully coming to them?

According to the media reports, people’s lives had been at risk to save money and increase profits. And the old founder seemed directly implicated. But the old founder hadn’t offered any comments, despite being chased by numerous journalists.

I thought about all the defence attorneys of the world:

Everyone, even the bad guys, has the right to a solid legal defence. And we’re all better off for it because it safeguards our legal system and democracy.

Is everyone entitled to a rhetorical defence in the spirit of free speech and openness? I thought of myself as a defence attorney not in the court of law but in the court of public opinion. It was a romantic idea to make me feel a little bit easier.

Admittedly, I was also excited. Crisis communications as a PR practice can be thrilling and emotionally powerful.

We arrived at the old founder’s home, and the family member who had sent me the email led us upstairs to a makeshift conference room. The old founder was a no-nonsense man; he asked us to lay out our plan for managing the crisis.

Perhaps I had hoped for a coffee first, but as a senior adviser, I know when to get down to business and dispense with small talk.

“First,” I said, “we must get the facts and establish trust in our small group.”

The old founder seemed to appreciate my opener, so I kept going.

“Then, based on facts, we must develop a narrative that works for us. And within that narrative, we must find a lead. Change the lead, change the story.”

I continued: “We will also bring onboard legal counsel. If there’s any responsibility to be taken, we must publicly get out in front of the issue. This will include speaking with the media as soon as possible. It’ll likely be a good opportunity to empathise and acknowledge any pain and suffering — even if we cannot acknowledge any legal responsibility. In any case, we will make sure that you are prepared.”

The old founder was still calm and collected. I added:

“When the silence is broken, we’ll need to push for a parallel internal process in which your company takes a series of actions. Breaking the silence and speaking with the media will be tough, but speaking alone won’t be enough. We must demonstrate that your company is also doing something because of what’s happened. Actions speak louder than words.”

I felt that I had the floor, so I pressed forward:

“With the silence broken and your company taking action, our focus will be to ride the wave and make solid tactical decisions based on sound judgement and constant media monitoring. It’ll be tough, but you’ll ride out the worst storm by being publicly available and accommodating. Once out of the immediate storm, we begin restoring the brand’s trust.”

The old founder gathered that I was about done, so he cleared his throat and got ready to say something, only to be interrupted by the participating family member:

She was upset.

And she went on to explain what had happened.

As it turned out, the old founder wasn’t guilty of malice. It was an employee who had broken the rules by mistake. Not for personal profit or gain, just a mistake. It could be easily proven, too. The employee had been loyal for decades, with only months to retire.

However, the news media had already gone two- or even three full circles, ripping the brand and the old founder to shreds. In the eyes of everyone reading a newspaper, the old founder was guilty.

I quickly glanced over at my PR colleague, and I’m sure her thoughts were roughly the same as mine. In my head, it sounded something like this:

“So, we present evidence of the mistake and disproof any allegations of malice or undue profiteering; that’s our new lead. We apologise and compensate those affected, and we fire the employee. We establish new protocols to ensure the same mistake can never happen again. And then we take it from there.”

But the old founder, almost as if he was able to read my mind, finally spoke:

“No,” he said.

The employee who had made a mistake was one of the company’s first employees. The old founder refused to hang this loyal coworker out to dry, especially with only a few months to retirement.

“The negative media would crush him and his family,” he said.

“But I… I can take it.”

And take it, he did. New security protocols were implemented to ensure that such mistakes could never happen again. Affected parties were handsomely compensated. And during all this, the old founder took full responsibility, apologised, and retired. He left his company to younger family members.

And the employee who made a mistake got to retire with a large celebration and a happy family.

The incident was discussed in the news media for quite some time afterwards. And everyone was sure that the owner was an evil older man — even later when the old founder was freed from legal charges.

Maybe the old founder made the right decision. Maybe he didn’t. Who knows? It was his decision, not anyone else’s. Ultimately, he took the blame and shame into retirement and allowed a new generation to start anew.

For a couple of months, my PR colleague and I did what we could to accommodate the old founder’s directions. And that’s that.

So, why am I telling you this story?

When a media story is based on what people have told journalists, you can never be 100% sure that what you’re being told is what truly happened. Some accounts are never challenged.

We would all benefit from remembering that there’s a reality behind and beyond the reported media narrative. Not all those portrayed as devils are evil. And not all those portrayed as saints are good.

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

PR Resource: The Public Apology

The Public Apology

A public apology is, by nature, an ambiguous statement; it ranges from submissive remorse to a chevalier’s trope of humbly expressing that the outcome was all that one could muster — despite best efforts.

“Public apologies function as ritualistic public punishment and humiliation, rather than forgiveness, to enforce ethical standards for public speech.”

Source: Rhetoric Society Quarterly 1Ellwanger, A. (2012). Apology as Metanoic Performance: Punitive Rhetoric and Public Speech. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 42, 307 — 329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02773945.2012.704118

The audience will not consider anyone’s public apology until they understand why someone did what they did and how they feel about doing it. This ambiguity is why saying, “I apologise” is never enough — you must also express regret and explain yourself.

Anatomy of an Apology

Types of Public Apologies

There are several different types of apologies to avoid. Unfortunately, as far as public apologies go, these types of public apologies are widely used — often with devastating PR consequences.

From a PR perspective, I recommend only one type of apology:

Moving Into the Next Stage

Apart from an honest delivery, this is what a wrongdoer must understand about the strategic use of a public apology as a strategic tool:

Public apologies are not a method of obtaining absolution or mitigating the loss of public trust. Forgiveness and trust must be earned separately and in the long term.

A public apology is a tool to allow the media narrative to move into the next stage sooner rather than later — whatever that stage might hold in store for the wrongdoer.

Learn more: The Public Apology

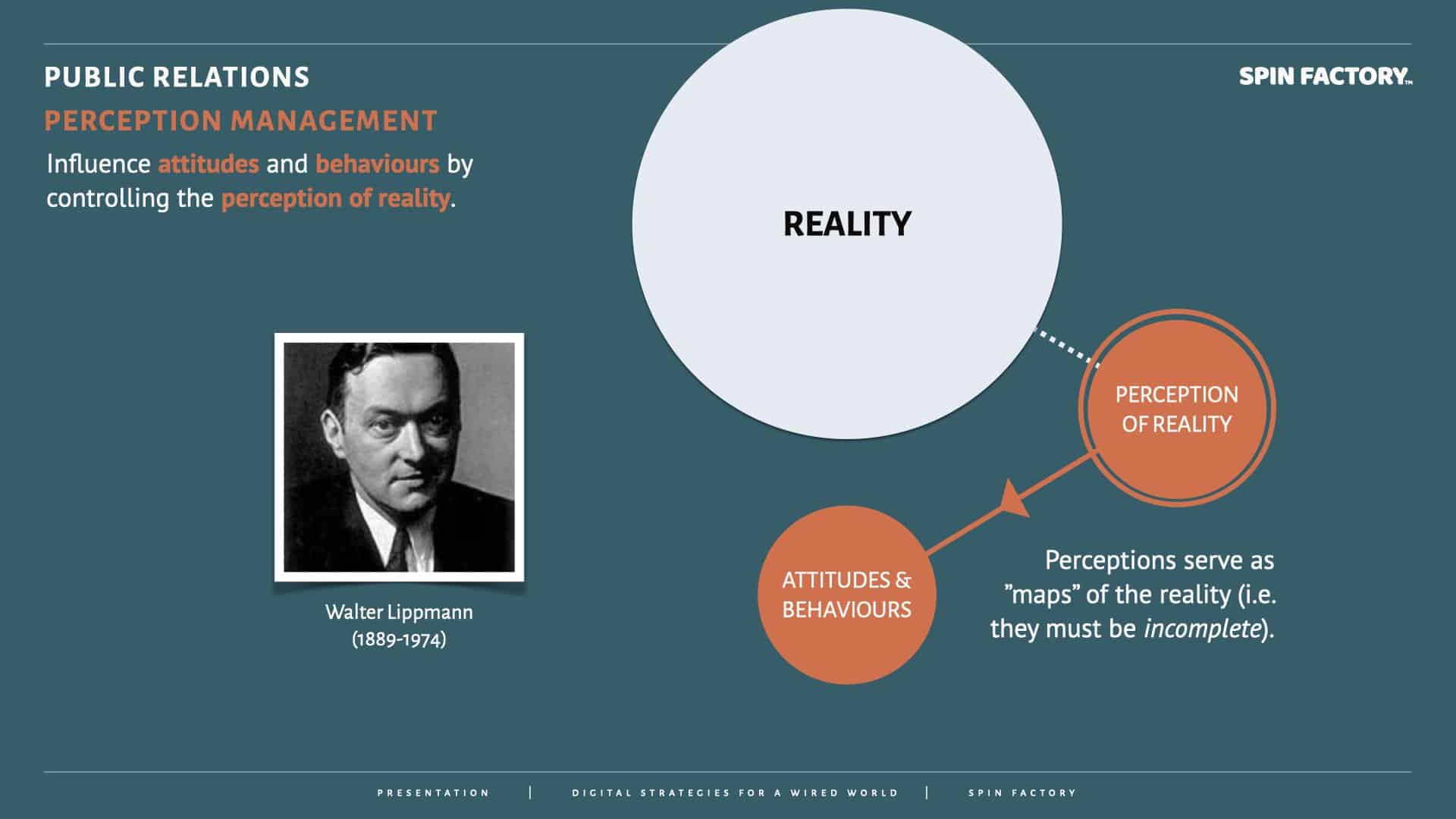

PR Resource: Perception Management

Walter Lippmann and Perception Management

In his seminal work Public Opinion (1922), Walter Lippmann laid the intellectual groundwork for the idea that perception and reality are not the same — a core principle of modern perception management. 2Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan.

Lippmann argued that:

Lippmann’s ideas resonate deeply with perception management in public relations.

“We are all captives of the picture in our head — our belief that the world we have experienced is the world that really exists.”

— Walter Lippmann (1889 – 1974)

On Creating Pseudo-Environments

Lippmann coined the term “pseudo-environment,” which describes the filtered, biased, and often artificial version of reality presented by the media. He warned that influential elites could exploit this manufactured reality to manipulate public thought and behaviour.

Lippmann was sceptical about the public’s ability to discern reality from the pseudo-environment, which raises ethical concerns:

Perception management is not inherently sinister, but as Lippmann warned, it places immense power in the hands of those controlling the narrative.

In essence, perception management is the applied PR version of Lippmann’s media critique. It acknowledges that facts alone do not win public trust—priming, framing, storytelling, and emotional appeal do.

Learn more: Perception Management

Annotations

| 1 | Ellwanger, A. (2012). Apology as Metanoic Performance: Punitive Rhetoric and Public Speech. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 42, 307 — 329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02773945.2012.704118 |

|---|---|

| 2 | Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan. |