Walter Lippmann’s ideas have heavily influenced PR.

Walter Lippmann, one of the most prominent American journalists and political commentators of the 20th century, left an indelible mark on media, public opinion, and democracy.

His intellectual legacy continues to shape our understanding of media’s role in society, the formation of public opinion, and the functioning of democratic institutions.

Here we go:

Walter Lippmann and Public Opinion

Born in 1889 in New York City, Lippmann began his career in journalism at an early age, writing for various publications before eventually becoming a co-founder of The New Republic.

Over the course of his illustrious career, Lippmann penned numerous books, essays, and newspaper columns, grappling with some of the most pressing issues of his time.

Central to Lippmann’s work was his exploration of the relationship between media and democracy.

In his seminal book, “Public Opinion” (1922), Lippmann dissected the process through which news is disseminated and consumed, arguing that the media shapes public perception of reality by constructing a “pseudo-environment” that often distorts the truth. This idea, which highlighted journalism’s limitations and potential biases, underscored the importance of accurate reporting and the need for a well-informed citizenry in a functioning democracy. 1Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan.

Lippmann’s contributions to our understanding of media, public opinion, and democracy have impacted journalism, political science, and communication studies.

His insights into the power dynamics in the media landscape, the limitations of public knowledge, and the responsibilities of the press in a democratic society remain as relevant today as they were during his lifetime.

In the constantly evolving media landscape, Walter Lippmann’s ideas on the interplay between media, public opinion, and democracy provide a valuable framework for understanding the challenges and responsibilities that both media organisations and individual citizens face.

By drawing on Lippmann’s insights, we can strive to create more informed, engaged, and critical publics capable of navigating the complexities of the modern information landscape and holding decision-makers accountable in pursuing a healthy, functioning democracy.

Learn more: Walter Lippmann and Public Opinion

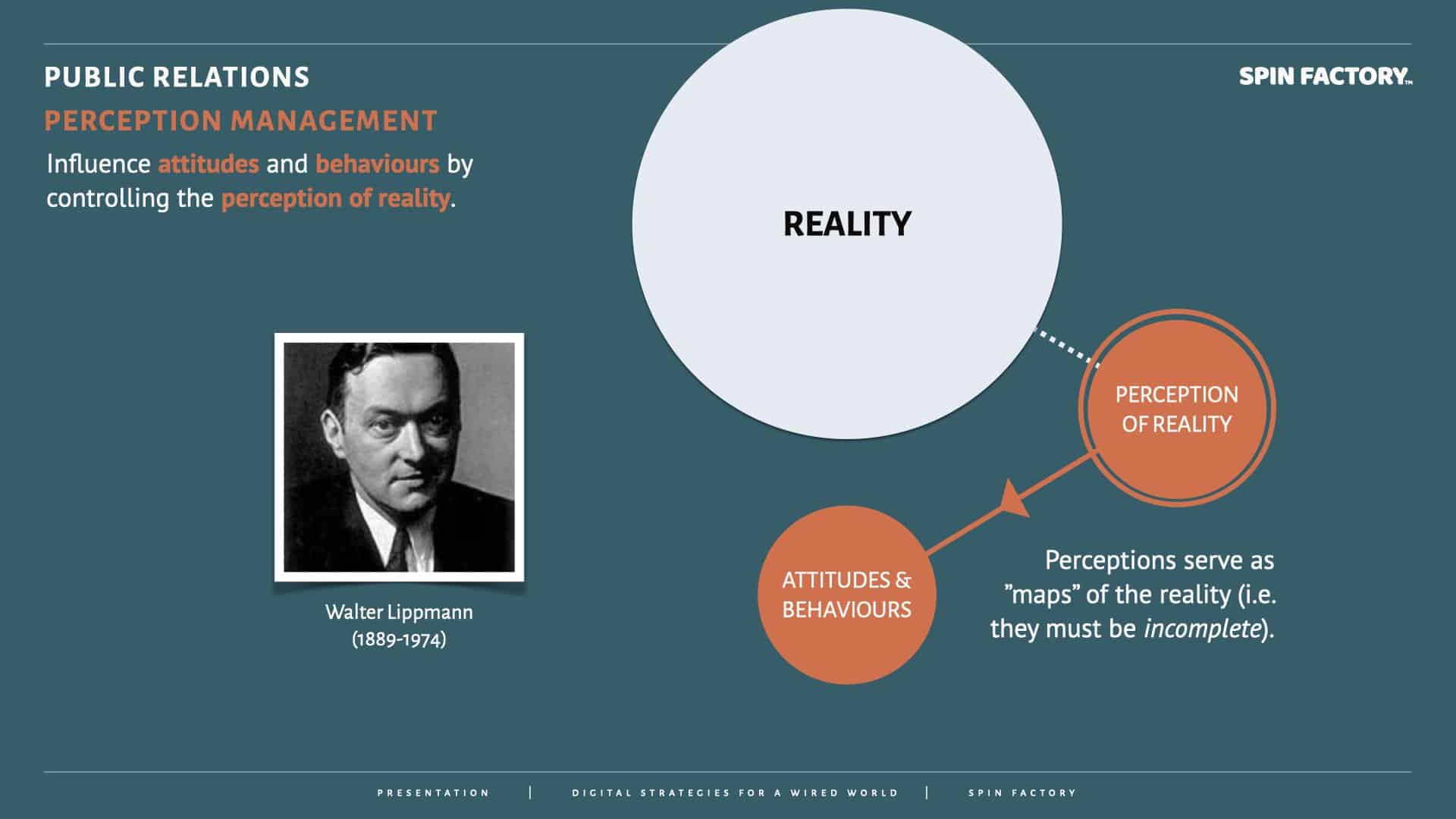

Walter Lippmann and Perception Management

In his seminal work Public Opinion (1922), Walter Lippmann laid the intellectual groundwork for the idea that perception and reality are not the same — a core principle of modern perception management. 2Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan.

Lippmann argued that:

Lippmann’s ideas resonate deeply with perception management in public relations.

“We are all captives of the picture in our head — our belief that the world we have experienced is the world that really exists.”

— Walter Lippmann (1889 – 1974)

On Creating Pseudo-Environments

Lippmann coined the term “pseudo-environment,” which describes the filtered, biased, and often artificial version of reality presented by the media. He warned that influential elites could exploit this manufactured reality to manipulate public thought and behaviour.

Lippmann was sceptical about the public’s ability to discern reality from the pseudo-environment, which raises ethical concerns:

Perception management is not inherently sinister, but as Lippmann warned, it places immense power in the hands of those controlling the narrative.

In essence, perception management is the applied PR version of Lippmann’s media critique. It acknowledges that facts alone do not win public trust—priming, framing, storytelling, and emotional appeal do.

Learn more: Perception Management

The Manufacturing of Consent

Walter Lippmann’s concept of the “manufacture of consent” illustrated the power dynamics in the media landscape.

Lippmann argued that a small group of elites, whom he called the invisible government, wielded significant influence over public opinion by controlling the narrative presented in the media. This idea laid the groundwork for future theories on media manipulation and the role of propaganda in shaping public discourse.

At the same time, Lippmann was acutely aware of the challenges facing the average citizen in making sense of the complex world around them. He posited that individuals often rely on stereotypes (i.e. simplified mental constructs to process information and make decisions), which can lead to biases and misconceptions.

These “stereotypes” have profound implications for how media organisations present news and how individuals interpret it, emphasising the need for critical thinking and media literacy in navigating the modern information landscape.

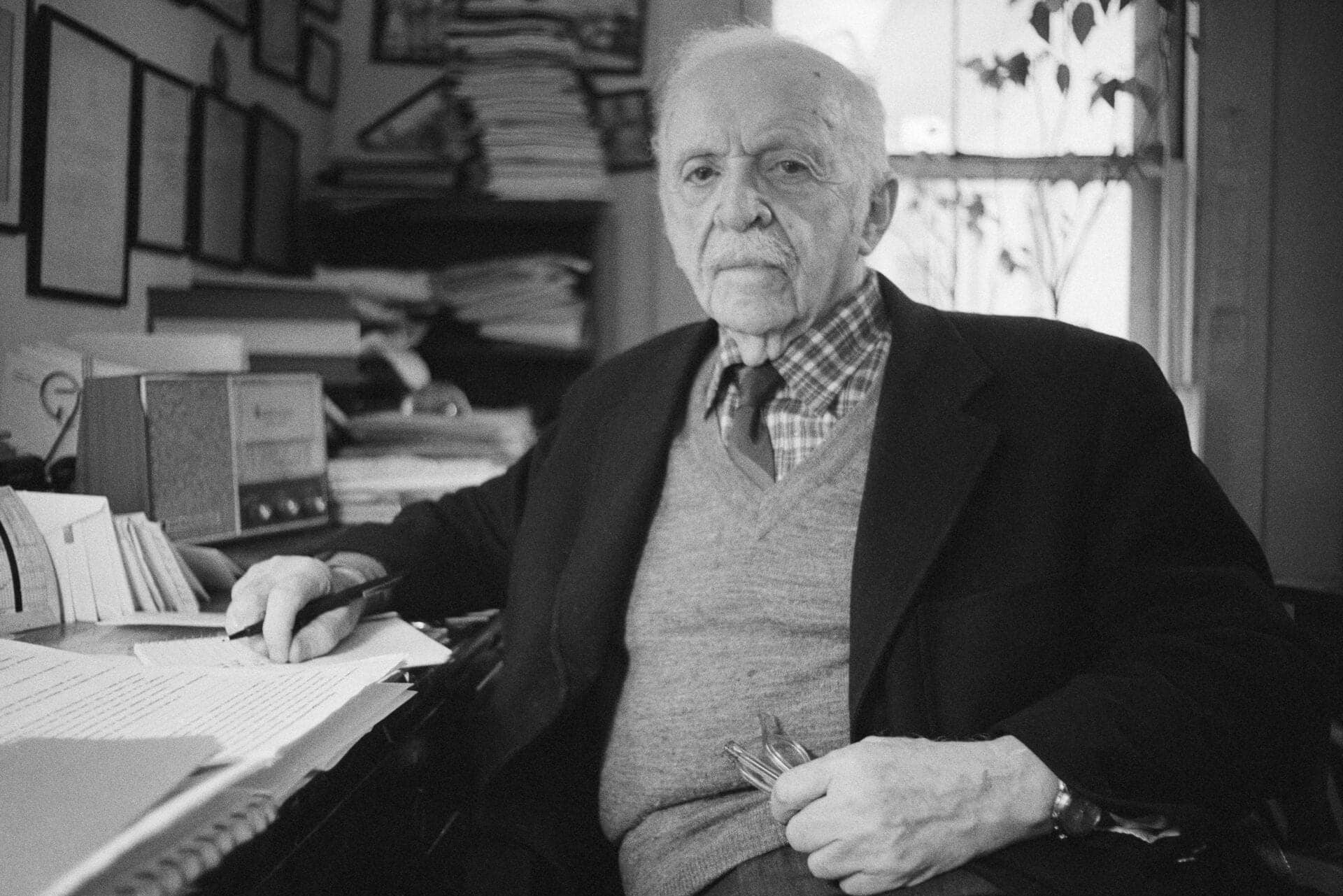

Chomsky and Herman’s Radical Expansion

Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman took Lippmann’s idea and radicalised it in Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988). They argued that media does not just inform — it serves as a propaganda system that maintains élite control by systematically filtering information in ways that serve powerful interests.

Chomsky and Herman criticised the “manufacture of consent” as an anti-democratic process that manipulates the public against their interests.

The book introduced the propaganda model, which explains how corporate ownership, advertising, government influence, and ideological bias shape mass media to support élite agendas.

Rather than seeing perception management as a tool for stability (as Lippmann did), Chomsky and Herman viewed it as a mechanism of control, deception, and suppression of dissent.

Learn more: The Manufacturing of Consent (to be published)

The Omnicompetent Citizen

Despite his scepticism about the general public’s ability to meaningfully engage with the complexities of contemporary issues, Walter Lippmann remained a staunch advocate for democratic principles.

In his later work, The Phantom Public (1925), Lippmann grappled with the concept of the omnicompetent citizen and the role of public opinion in democratic governance. He contended that while the average citizen may not possess the expertise necessary to influence policy decisions directly, they still have the power to hold decision-makers accountable through the ballot box. 3Lippmann, W. (1925). The phantom public. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Lippmann’s ideas on the role of journalism in democracy also extended to his advocacy for a responsible and ethical press. He was a key proponent of objective journalism, arguing that reporters should strive to provide unbiased, factual information to their audiences.

THANKS FOR READING.

Need PR help? Hire me here.

Suggested Literature

Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Lippmann, W. (1925). The phantom public. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Steel, R. (1980). Walter Lippmann and the American Century. Little, Brown and Company.

Schudson, M. (2008). Why democracies need an unlovable press. Polity.

McNair, B. (2011). An introduction to political communication (5th ed.). Routledge.

What should you study next?

Spin Academy | Online PR Courses

Influencing PR: Notable Contributors

It’s noted that the gender bias is apparent here. I’m currently researching a more balanced list.

Public Relations Contributors

Learn more: All Free PR Courses

💡 Subscribe and get a free ebook on how to get better PR.

Annotations

| 1 | Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Lippmann, Walter. 1960. Public Opinion (1922). New York: Macmillan. |

| 3 | Lippmann, W. (1925). The phantom public. Harcourt, Brace and Company. |